Extreme Environments and Health

This blog is a largely freeform exploration by Filip Maric* (PhD), Associate Professor at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, with special interests in critical physiotherapy, sustainable healthcare, planetary health, philosophy and environmental post/humanities. It does not present fully researched insights but, rather, speculation about intersections between extreme environments and health and a resulting research agenda.

*Associate Professor, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1265-6205. Contact: filip.maric@uit.no

Extreme environments and human health relate to each other in many different, sometimes contradictory ways. Intuitively, a straightforward way to describe the relationship might be described by reducing their relationship as much as possible by way of separation. Extreme environments like outer space, the deep sea, extremely high- or low-temperature environments, high altitudes, etc., pose substantial risks to human health and are to be avoided in favour of health (provided lacking evolutionary, technological, sociocultural, or other changes) (Xu et al., 2020; Selby et al., 2024)

In earlier times, human (hominin?) awareness of the dangers of extreme environments might have inferred the existence of supernatural conditions, monsters, infinities of no return, unknown horrors, etc., all of which functioned as both discouragement and warning to maintain the separation between humans and extreme environments, for the sake of health.

Yet, it is likely also precisely the lure of the unknown, the strange, and the extreme that has long spurred excitement, curiosity, and the drive to venture to precisely those seemingly forbidden, out-of-reach and potentially unhealthy places (though necessity will undoubtedly also long have been a critical driver). Whether as a part of rites-of-passages, the pure indulgence of adventure, for the sake of treasures, fame, or else, humans have sought out extreme environments over many centuries, if not millennia, and continue to do so until today. At varying costs and benefits for health.

Barring the case of sheer necessity, we might postulate that the relationship between extreme environments and health was and is dramatically changed, not only by way of proximity but also by daring and privilege, with the two potentially being difficult to discern. Where humans have actively sought out extreme environments, health is not only a question of those who would venture to expose themselves to these extremes but also those who could…because they have the abilities, technologies, finances, and other means to do so.

The advent and history of tropical medicine, public health, and global health are undeniably tied to privilege(and power or might, as inherent in it) in more ways than one (Bashford, 2003; Neill, 2012; Greene et al., 2013). Colonialism was all about exploration and expansion into the previously unknown, strange, and extreme, and so is always inseparably tied to the need for medical invention to inoculate colonisers from the ‘extremes’ of new environments, tropical, desert, highland, marine, or else (all while weaponising disease to subdue the colonised). Increased knowledge of the ‘treasures’ hidden within the previously extreme, would have increased the need for medical innovation to facilitate extraction without risking health, and additionally removed the sense of ‘extremeness’ of many of these environments via knowledge and the assurance of safety (i.e. health).

The deep link between health, extreme environments, and privilege, can also be observed in other, seemingly benevolent human activities like science and adventure sports. Think of the long queues of mountaineers wishing to reach the summit of Everest, K2, and other such peaks of adventurous prowess. And then think of the oxygen tanks that enable physical functioning in higher altitudes, or sherpas carrying loads that would otherwise lead to injury and overuse in untrained bodies, or even just the ever more sophisticated equipment from shoes, clothing, sunglasses, and you name it, all coming at a cost that is prohibitive for most of the global population. Or think of sports or scientific diving and all the gear and costs required to reach the fascinating depths at which those who can afford it can observe one or other marine animal or environment; and then the hyperbaric chambers that appear as a matter of course when health is in question after things have gone wrong. The list goes on.

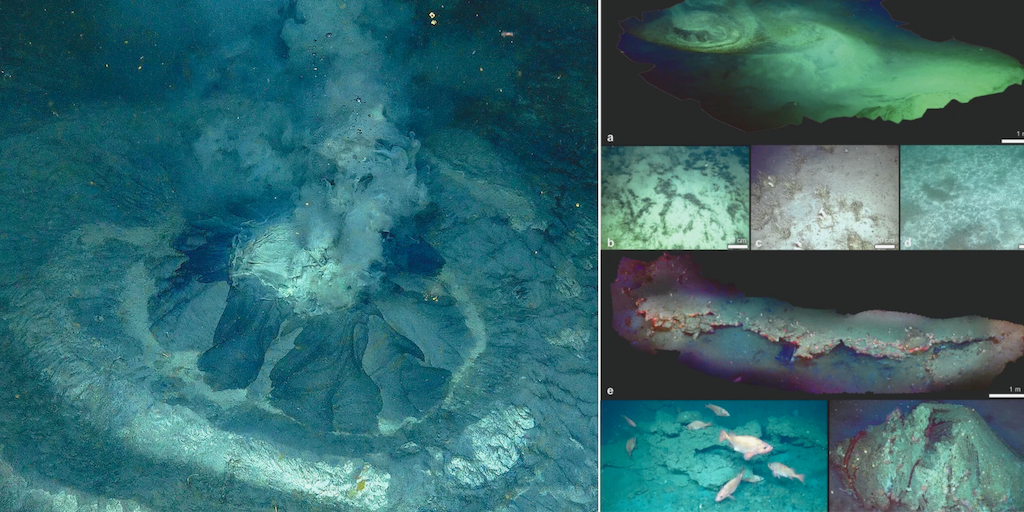

But if tropical medicine, extreme medicine, expedition medicine, wilderness medicine, etc., have long been tied to fancy and privilege, we should also keep in mind that what are extreme environments to some, have also long been the home to many others, marking yet another facet in the manifold relationships between extreme environments and health. The high fertility and nutrient richness of soil around volcanoes have made them a preferable location for human settlements for many centuries, and despite all associated dangers. Seemingly further removed mud volcanoes provide the foundation for thriving communities of biodiversity deep under the Arctic Sea (Panieri et al., 2025). Deserts make up the home of complex, more-than-human networks of cohabitation. And so here also, the list goes on.

What increasing knowledge about our planetary ecosystem has also taught us is the extent to which extreme environments have been critical to maintaining the relatively stable environmental conditions that humans have enjoyed throughout the Holocene (Steffen et al., 2015). Arctic Sea Ice, now on a fast track to disappearing, has had a critical role in maintaining ocean currents. Oceans themselves constitute the world’s largest carbon sinks and so critically support climate regulation, famously alongside tropical rainforests like the Amazon, which in turn gets fed nutrients from the desert (Garner, 2015). Look at it this way, and we must recognize that extreme environments have always already been much closer to home than we thought and so much more fundamental to health than we would think on the surface, irrespective of how far away they might seem.

To our great disadvantage, human-driven climate change, biodiversity loss, and large-scale environmental degradation are now making this latter relationship an ever more proximal one. Floods, wildfires, heatwaves, hurricanes, blizzards, landslides, and other increasingly frequent and intense extreme weather events are already the new normal nearly everywhere around the world. As the everyday environments people live in increasingly become extreme environments, the health of people is increasingly at peril. Those exposed to extreme environments, then, are no longer those privileged enough to find themselves in this situation but, lacking the necessary means and privileges, simply the vulnerable. Thus, today, extreme medicine (properly conceptualised) might no longer be a matter of privilege but an urgent and fundamental need for people everywhere around the world.

If the study of the relationship between extreme environments and health seemed like a faraway special interest, then it should be clear we need to change our perspective. In difference to previous approaches to extreme health, however, the challenge at hand might not only be to understand the many ways that extreme environments and health are interconnected and can and should be met, but how to ensure that neither this knowledge nor its benefits become a matter of privilege (Gupta et al., 2024). It strikes me that this seems doubly important at a time at which not only extreme ecological conditions are increasingly affecting the health of people, but also social ecologies are increasingly becoming extreme again, as if history has not taught us that it is mutual aid might be the strongest predictor for health, also under extreme conditions (Kropotkin, 1902).

References

Bashford, A. (2003). Imperial Hygiene: A Critical History of Colonialism, Nationalism and Public Health. Palgrave Macmillan.

Garner, R. (2015). NASA Satellite Reveals How Much Saharan Dust Feeds Amazon’s Plants. Nasa. https://www.nasa.gov/missions/calipso/nasa-satellite-reveals-how-much-saharan-dust-feeds-amazons-plants/

Greene, J., Basilico, M.T., Kim, H. & Farmer, P. (2013). In Farmer, P., Kim, J.Y., Kleinmann, A., & Basilico, M.T. (Eds.) Reimagining Global Health: An Introduction (pp. 33-73). University of California Press.

Gupta, J., Bai, X., Liverman, D. M., Rockström, J., Qin, D., Stewart-Koster, B., Rocha, J. C., Jacobson, L., Abrams, J. F., Andersen, L. S., Armstrong Mckay, D. I., Bala, G., Bunn, S. E., Ciobanu, D., Declerck, F., Ebi, K. L., Gifford, L., Gordon, C., Hasan, S., … Gentile, G. (2024). A just world on a safe planet: a Lancet Planetary Health–Earth Commission report on Earth-system boundaries, translations, and transformations. The Lancet Planetary Health, 8(10), e813–e873. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(24)00042-1

Kropotkin, P. (1902). Mutual aid: A factor of evolution. Mutual aid: A factor of evolution. McClure Phillips & Co.

Neill, D.J. (2012). Networks in Tropical Medicine: Internationalism, colonialism, and the rise of a medical specialty, 1890-1930. Stanford University Press.

Panieri, G., Argentino, C., Savini, A. et al. (2025). Sanctuary for vulnerable Arctic species at the Borealis Mud Volcano. Nature Communications, 16, 504. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55712-x

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., Biggs, R., Carpenter, S. R., De Vries, W., De Wit, C. A., Folke, C., Gerten, D., Heinke, J., Mace, G. M., Persson, L. M., Ramanathan, V., Reyers, B., & Sörlin, S. (2015). Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347(6223), 1259855–1259855. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1259855

Selby, J., Hulme, M., Cramer, W. (2024). There is no human climate niche. One Earth, 7(7), pp.1155-1157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2024.06.009

Xu, C., Kohler, T. A., Lenton, T. M., Svenning, J.-C., & Scheffer, M. (2020). Future of the human climate niche. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(21), 11350–11355. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1910114117