PhD / researcher

PhD / researcher

For literature studies at this level, the full methodology of systematic reviews is utilized. We recommend making the research question as precise as possible.

Be aware that the literature search is only a small part of the total methodology that should be used when conducting a systematic review.

In our examples, we present a sensible solution for a literature search tailored to the research question. We want to emphasize that there is never a definitive answer for literature searches, and that multiple solutions can be effective.

Example from Medline & Embase

We base this on the following example of a project:

The purpose of the project is to find out how accurately frontline healthcare physicians can detect heart valve diseases using auscultation. A possible title could be:

Diagnostic accuracy of heart auscultation for detecting valve disease

Step 1: From research question to searchable terms

A simple method to use when defining the main search keywords for your project is to ask yourself the following question: What main elements from my project do I want to find in relevant publications?

The main elements in our example are:

- Heart auscultation

- Diagnostic accuracy

- Detecting valve disease

To systematize these main elements and find the correct scientific terms, we recommend setting the main elements as headings of individual "boxes." This provides a clear overview of the individual search keywords and helps you conduct the search in a systematic and structured manner.

Step 2: Find search keywords for each main element

Now you can start the process of finding the correct scientific search keywords. There are many different methods to use. For example, you can ask a supervisor, a fellow student, look up terms in a medical dictionary, or ask your supervisor for relevant articles and look them up in the relevant database, where you can easily find the controlled search keywords with which these are indexed. If you are an experienced researcher with a good understanding of the subject's terminology, there is an effective method to quickly find references of interest and then check the indexing of these references in relevant databases.

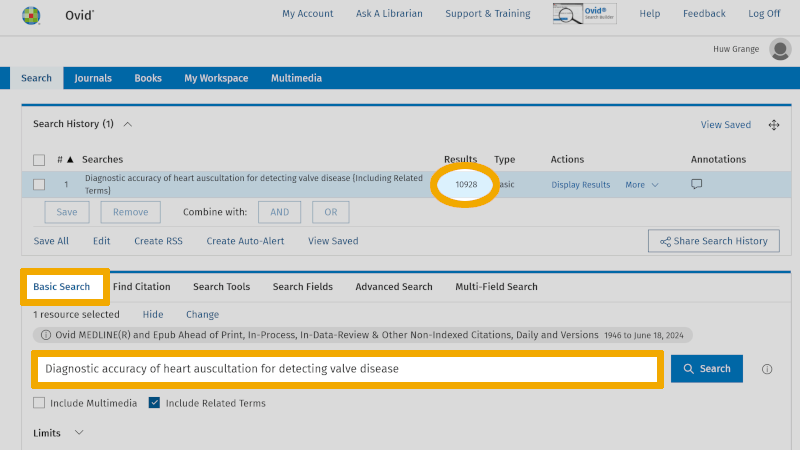

For instance, you can copy the title of the project and paste it under the 'Basic Search' heading in, for example, Medline.

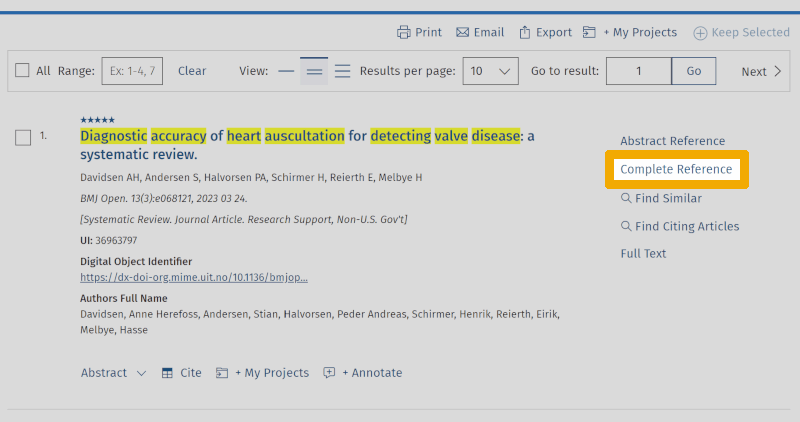

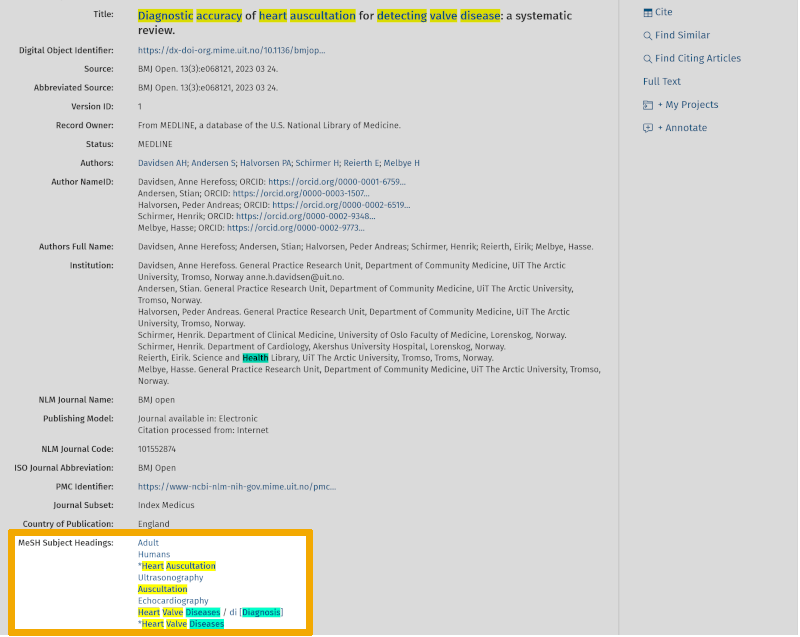

'Basic Search' in Medline allows you to search with natural language, much like in Google Scholar. As you can see, you get over 10,000 references. Medline will sort these references and place the most relevant ones at the top of the results list. Therefore, it may be worthwhile to go through the top 10-20 most relevant references to check how they are indexed. Here you will find relevant controlled and free search keywords that can be used in your own search under the 'Advanced Search' tab. By clicking on the 'Complete Reference' button, to the right of a relevant article title, you are taken to the page showing the abstract and which MeSH terms (Medical Subject Headings) the particular reference is indexed with.

During the initial work of finding relevant search keywords and getting an overview of the terminology used within the chosen theme, you will almost always find that several explanatory terms can be used under each main element. These are the first and second steps in the 5-step method of building and conducting a structured and systematic search, which always takes time and requires a lot of work.

In our example, we find the following words:

- Heart auscultation, Heart murmurs, Heart sounds

- Sensitivity and specificity, Observer variation

- Echocardiography

We now fill in these words in our "boxes" and get the following setup for our search:

As a researcher/PhD student, you are expected to run your search in the most relevant reference databases. If you are unsure which databases are the most relevant, you can contact the University Library, or discuss this with your supervisor or your colleagues. For this specific project example, we recommend Ovid Medline, and Ovid Embase Classic+Embase, as the most relevant databases. It would also be wise to check the Cochrane database for updated literature reviews.

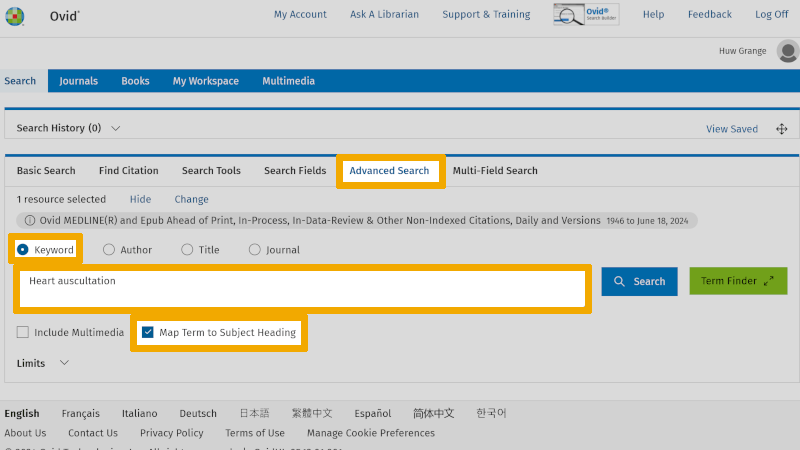

We start our first search in Ovid Medline. The first thing we do in Medline is to look up all the translated search keywords under each main element in the controlled search vocabulary (MeSH, or Medical Subject Headings). This is a very important step in the process because we should always use controlled search keywords if such exist for the relevant main element. If you are unsure what a controlled search vocabulary is and what advantages it offers, you should look at our page about controlled search keywords again.

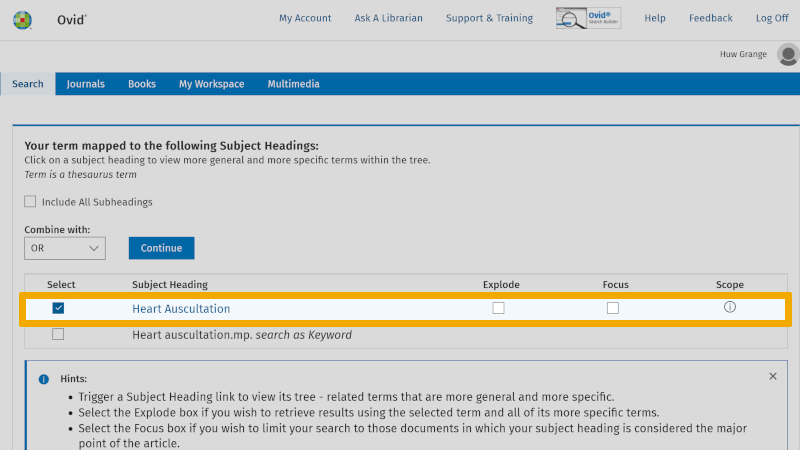

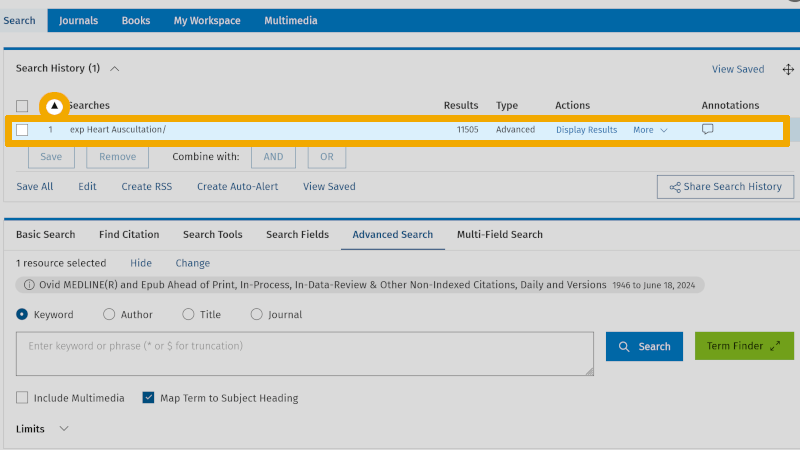

Here exemplified with the first search keyword in our first box, 'Heart auscultation'. In the search window above, you will see that 'Keyword' and 'Map Term to Subject Heading' are checked. This is the default setup in Medline and ensures that Medline searches in the controlled search vocabulary for the word written in the search window.

In the search window below, you find that your search on 'Heart auscultation' found the controlled search keyword 'Heart auscultation' (MeSH term).

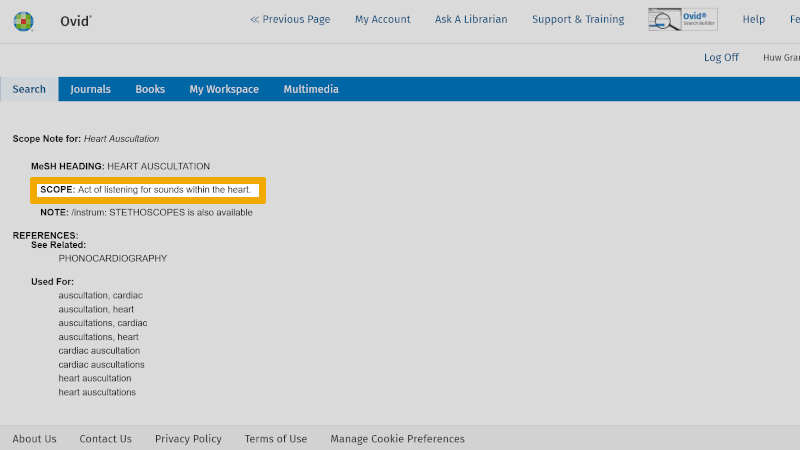

You should always check the definition of the controlled search keyword that is suggested. You do this by clicking on the information symbol to the right of your controlled search keyword. You find this under the heading 'Scope'.

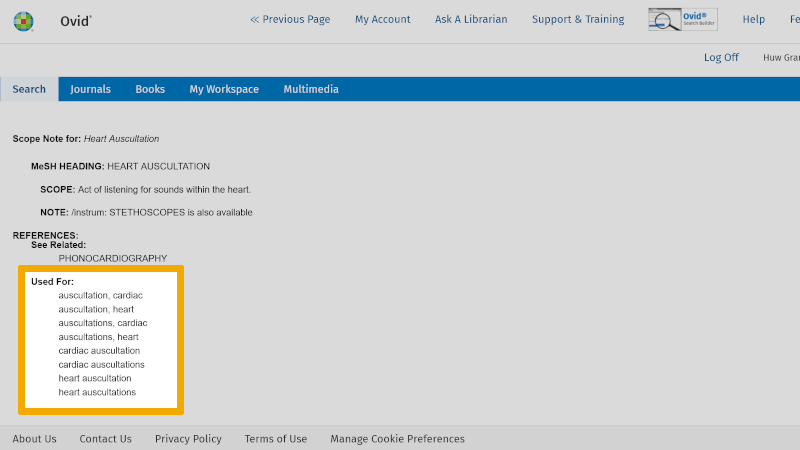

Here you read the objective definition of this controlled search keyword.

Note: Under the heading 'Used For:' in this window, you will always find an overview of synonyms that can be used as free search keywords. You should also consider using these in your search. In connection with systematic literature reviews, the search should be improved by also using some synonymous free search keywords. Indexing of articles with controlled search keywords, such as MeSH terms, takes time. Hence, there may be delays of months, or longer. In addition, errors can occur in the indexing. Therefore, it is always good to build a literature search that also includes one or more free search keywords, in addition to the controlled search keywords.

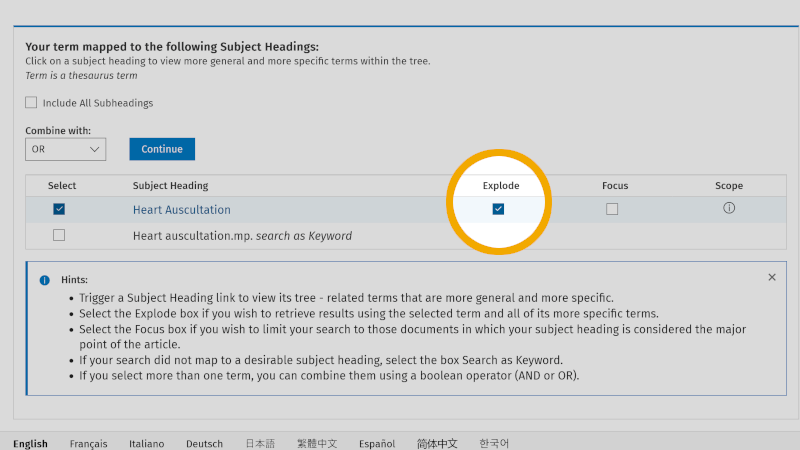

To ensure that you include all controlled search keywords further down in the hierarchical structure of the controlled search vocabulary, it is important that you check the box 'Explode' (see our page about controlled search keywords).

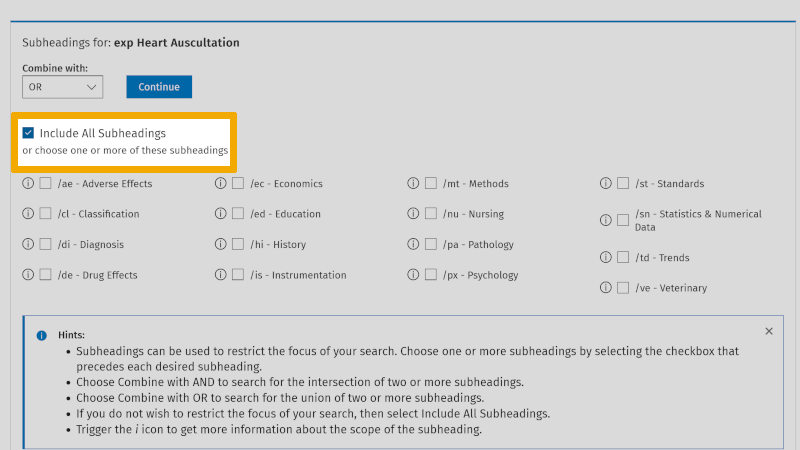

We then click on 'Continue', and are taken to the overview of subheadings. Here, you check 'Include All Subheadings', unless you want to focus on one or more of these.

Next, we click on 'Continue' and you now include all references that are indexed with the controlled search keyword 'Heart Auscultation'.

By clicking on the arrow symbol to the right of 'Search history', at the top left of the main menu, you can expand/collapse the search history. We see that 'Heart Auscultation', exploded, yields 11,505 references (exp Heart Auscultation/ 11505). We have now found the controlled search keyword for 'Heart Auscultation' (MeSH). We mark this in our box search setup:

We then continue by checking if the search keywords under each main element exist as controlled search keywords. We use the same procedure for each of the search keywords we have found so far.

Step 3: Build the first search

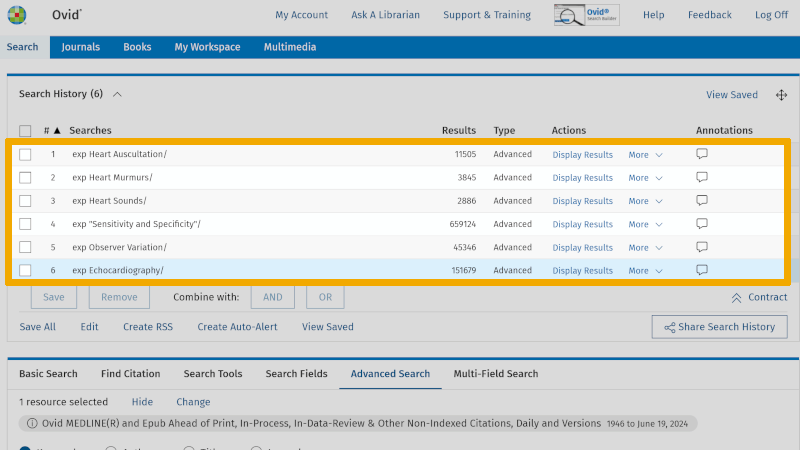

Now, you have found controlled search keywords for all the main elements in your project.

These can be found under 'Search History' on Medline's main page.

Some of you might think that the term 'Heart Auscultation' naturally belongs to the main element 'Detecting valve disease'. The reason for placing this term under our first main element 'Heart auscultation' is that it will capture articles that address both of these main elements, with the hope that such a search setup will be able to tell us something about the effectiveness of one of these main elements as compared to the other.

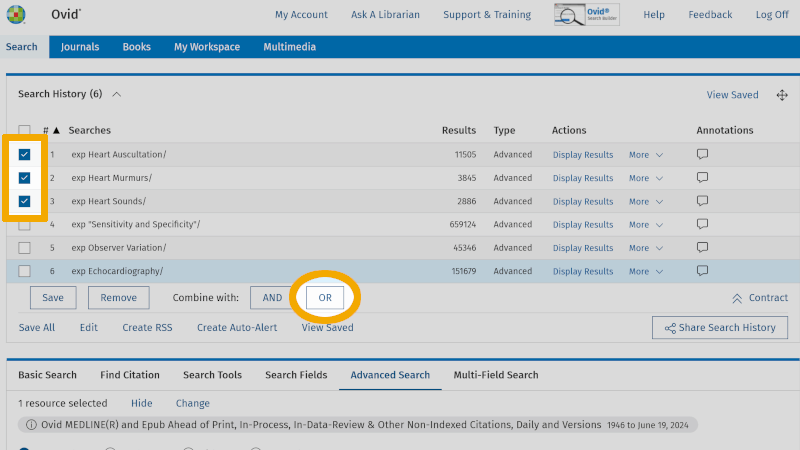

You are now ready to combine the controlled search keywords into a first literature search. Controlled search keywords from each main element are combined with OR in the following way. Check each of the controlled search keywords you have found in the first box.

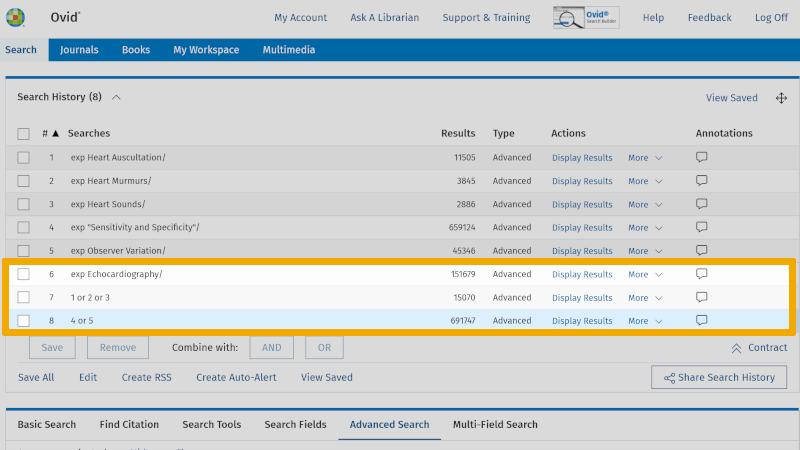

Then click on the Boolean operator OR, and you will see that these controlled search keywords combine in line 7 in 'Search History'.

Repeat this for the controlled search keywords you have found for the next two boxes. One box at a time! You will then find the combined search keywords for the three boxes, in lines 8, 7, and 6 respectively (which only has one controlled search keyword).

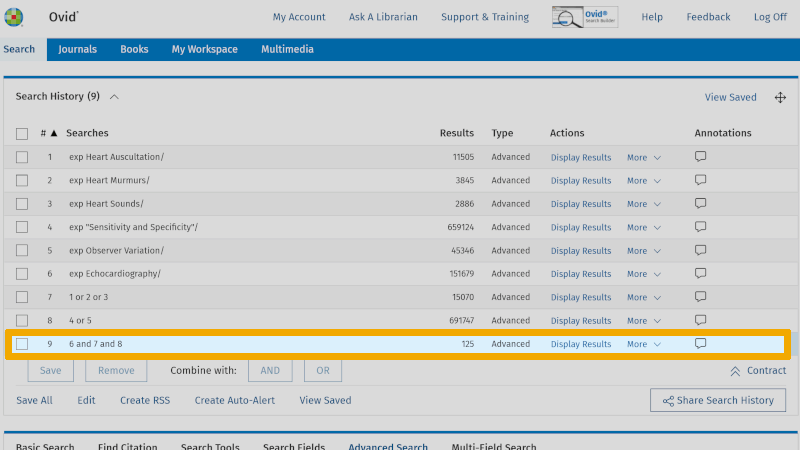

You are now ready to combine these three separate searches with AND. Check the lines 8, 7 and 6. Then click on the Boolean operator AND. You now see that your first search with controlled search keywords yields 125 references (line 9).

Step 4: Improve the search

The search we have conducted so far only used controlled search keywords for each main element from the project title. You can improve the search by using some synonymous free search keywords in what we call a text word search. Indexing articles with controlled search keywords, such as MeSH terms, takes time. Hence, there may be delays of months, or longer. Furthermore, minor errors can occur in the indexing. Therefore, it's always good to build a literature search that also includes one or more free synonymous text words, in addition to the controlled search keywords.

Let's start with our example:

Where can you find synonymous text words for these controlled search keywords?

One of the most important tools you have is actually to start by familiarizing yourself with the terminology of the scientific field you are working with. As a researcher/PhD student, you probably already have a relatively good overview of the terminology, but remember that databases index references from all over the world, and academic communities from different parts of the world may use synonymous terms for the controlled search keywords we have now found. A very useful tool is therefore to look up the individual search keyword you have found and placed in the box under each main element in the controlled search vocabulary. In Medline, this is the MeSH database, which we have previously used.

From the previous example above, you remember that each individual controlled search keyword has a precise explanation, here exemplified with ‘Heart auscultation’. Below ‘Used For’ you find synonymous free text words for the controlled search keyword.

As a researcher/PhD student, we recommend that you use as many free synonymous search keywords as possible. This increases the sensitivity of your literature search and will ensure that you find what is possible to find of relevant literature within the project's framework. Even if you are not conducting a systematic literature review, a structured and systematic search will give you a unique overview of current literature within your field.

Our first synonymous text word in our example is ‘cardiac auscultation*’.

Text word searches are done in selected search fields. The most common search fields we use in Medline are: ‘Title’, ‘Abstract’, and ‘Keyword Heading’ (authors' own keywords). We note this in our box setup, where we mark the three fields we will search in, with ti (‘Title’), ab (‘Abstract’), and kw (‘Keyword Heading’). The search syntax for the synonymous text word then becomes Cardiac auscultation*.ti,ab,kw. (Note the use of period and comma, and that no spaces are used.)

We use the same method for all the controlled search keywords. In addition, we should use other free search keywords we have picked up from various sources. We use the same syntax as described above.

By working structured and systematically as we have now demonstrated, we get the following box setup for our search.

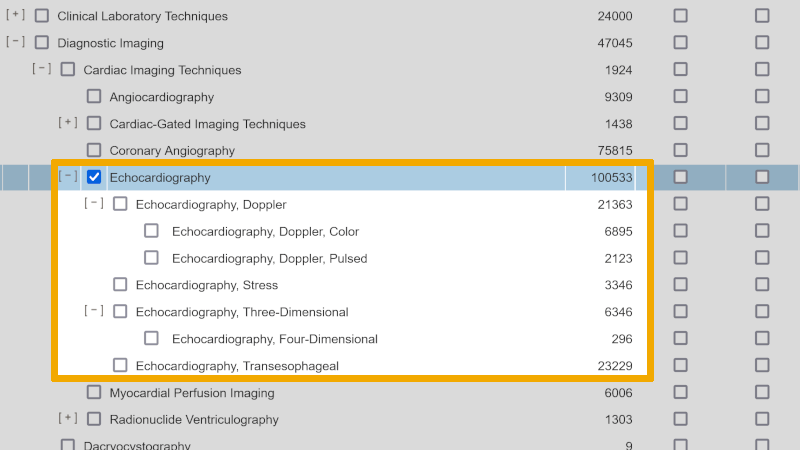

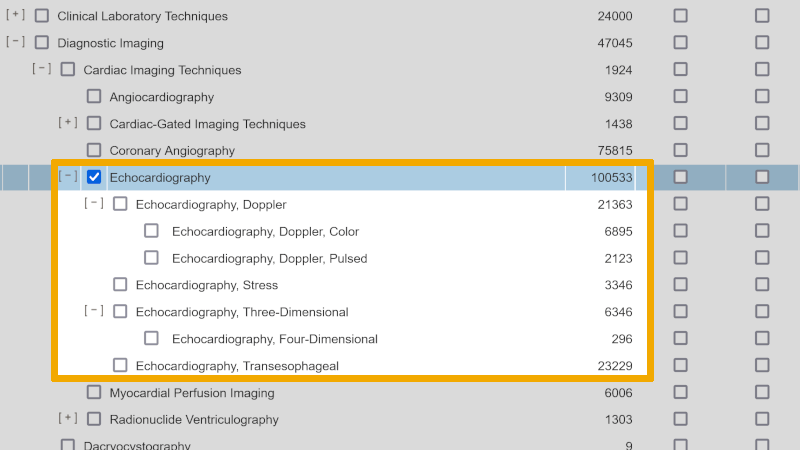

In the final search setup for this project, we have used most of the free synonymous text words we find by searching up the individual controlled search keywords in the controlled search vocabulary. In addition, we have used further free synonymous text words that we find in underlying controlled search keywords in the hierarchical structure of the controlled vocabulary. This is exemplified in the screenshot below, where you see the hierarchical structure of ‘Echocardiography’. Each of the underlying controlled search keywords will have one or more free synonymous text words that can be used in title/abstract/keyword searches. Here it is up to you conducting this search to make a professional assessment of how many, and which free synonymous text words you want to use. The more free synonymous text words in the search, the more sensitive it becomes. To further increase sensitivity, we also use ‘proximity searches’, using the operator ‘ADJ’.

What remains now is to perform this search in Medline. A good tip is to do this in a structured and clear manner. This means that you start with the search keywords in the box to the left and search up each keyword individually.

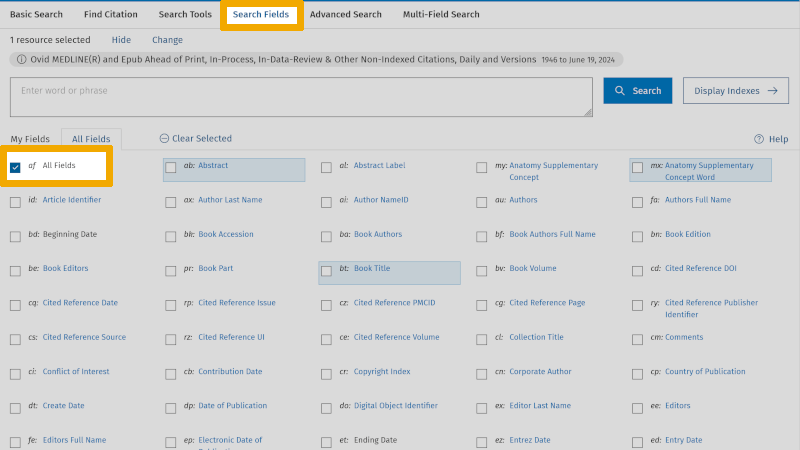

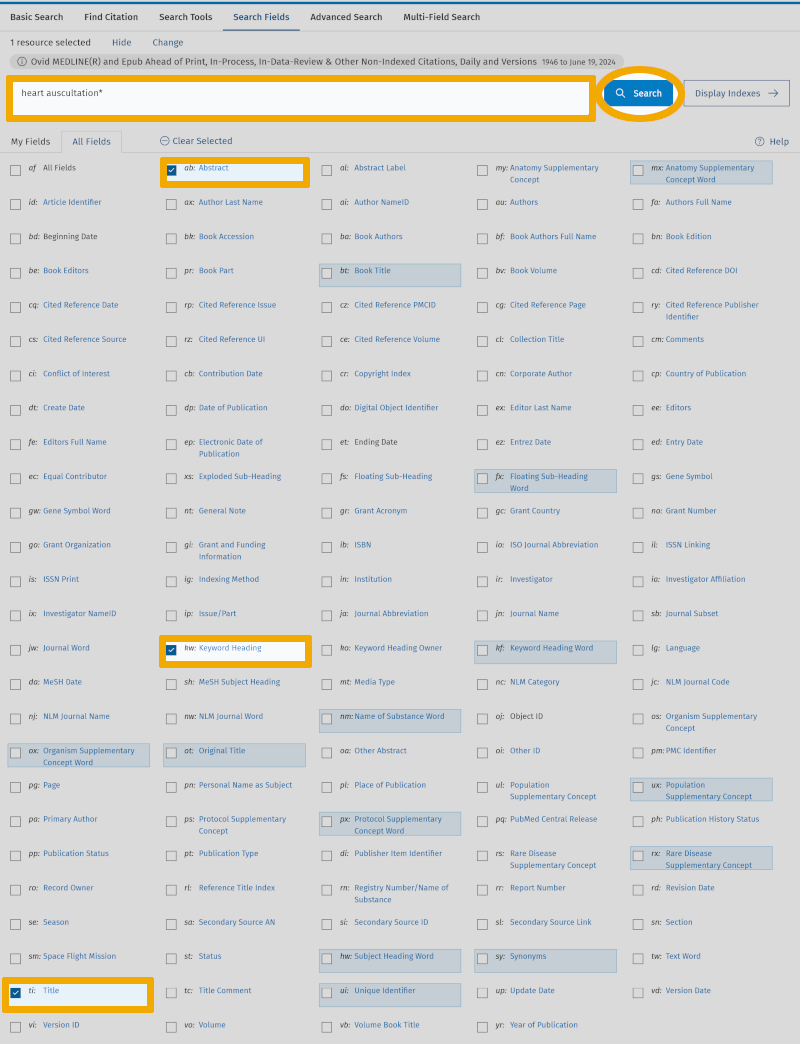

We start by searching up ‘Heart auscultation’. Then we click on ‘Search Fields’ (to the left of ‘Advanced Search’). Here we get an overview of all the text fields that each reference is indexed in. We also see that ‘All Fields’ is checked.

We uncheck ‘All Fields’ and enter our first synonymous text word: ‘heart auscultation*’, and check ‘Search Fields’: ‘Title’, ‘Abstract’, and ‘Keyword Heading’. Then we click on ‘Search’.

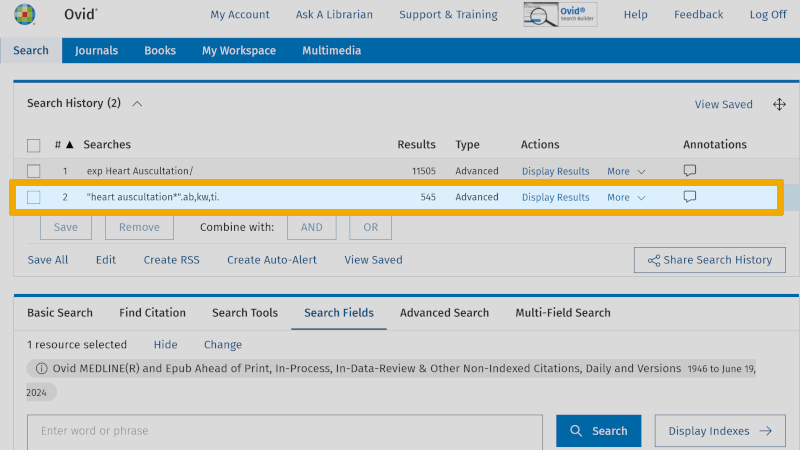

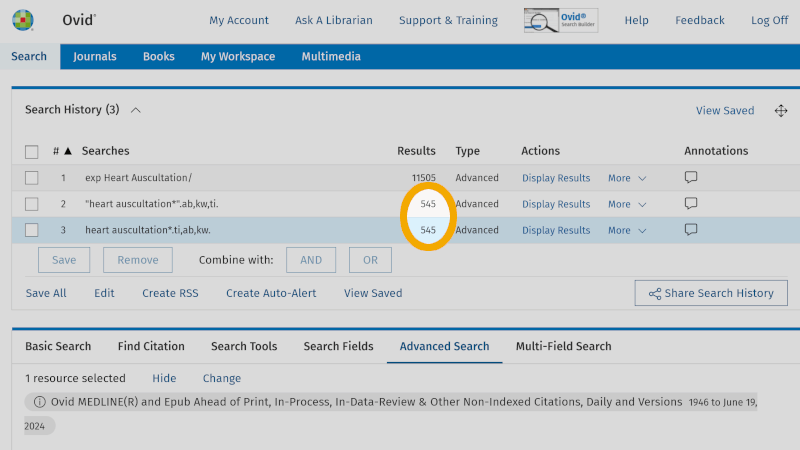

We then see that in Medline there are 545 references that have the text word ‘heart auscultation*’, in the title and/or abstract and/or authors' keywords.

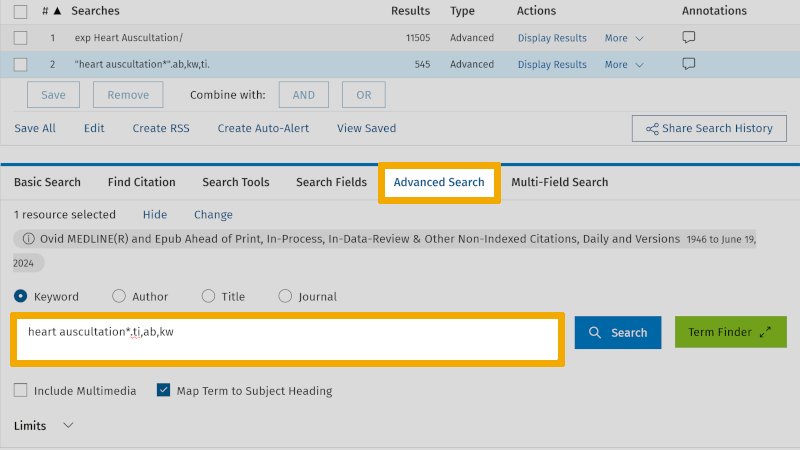

A practical tip is to conduct this 'Search Fields' search in the 'Advanced Search' screen. This way, you avoid having to click around on the various fields in the 'Search Fields' screen. You have now learned that the field codes for the three search fields, title, abstract, and authors' keywords, are respectively: ti ('Title'), ab ('Abstract'), and kw ('Keyword Heading'). You use these directly in the search window of 'Advanced Search', in this format: heart auscultation*.ti,ab,kw. (Note the use of period and comma, and that no spaces are used.)

When you click on the 'Search' button, you see that the result is the same (line 3 in the search history) as you got by going into 'Search Fields' (line 2 in the search history).

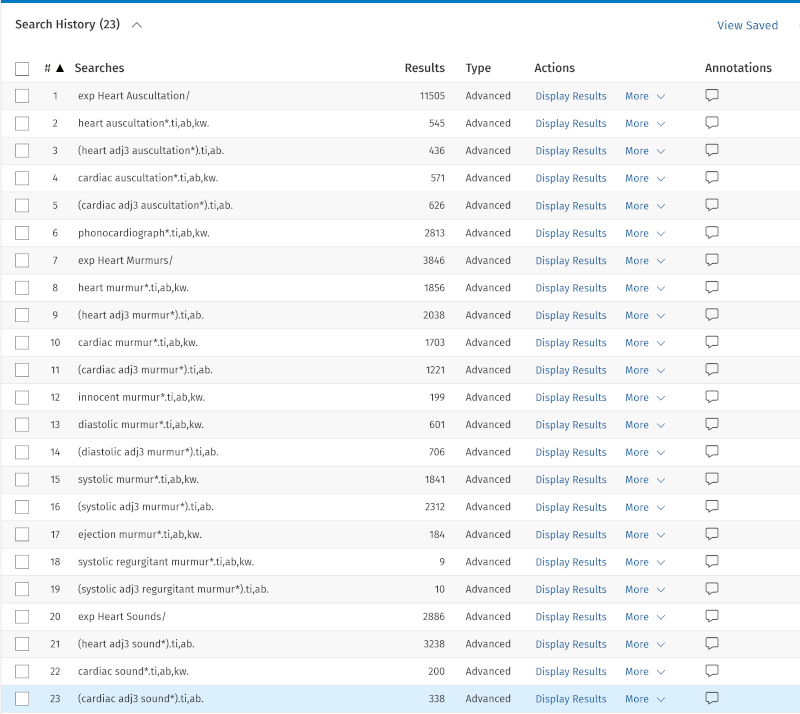

We now use the box setup we have come up with, and enter and look up one search keyword at a time. This provides a structured and systematic search history. In the screenshot below, you see all the search keywords retrieved from our first main element, or our first box if you will.

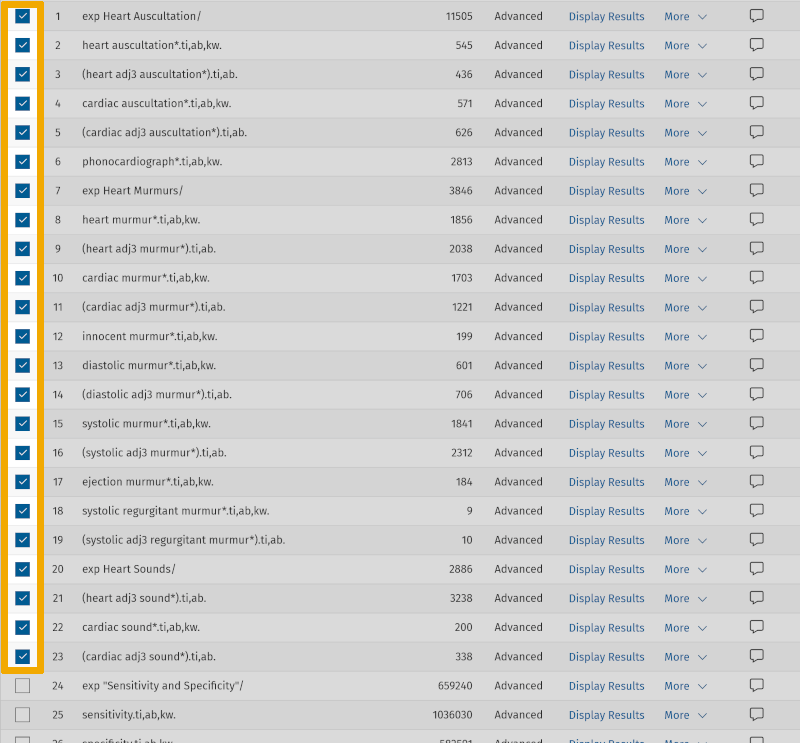

We are now searching for all the search keywords from our three main elements:

- 'Box 1' – lines 1–23

- 'Box 2' – lines 24–43

- 'Box 3' – lines 44–60

We are now ready to combine our improved search, by doing exactly the same as in step 3. We first select all the search keywords from the first 'box' under the main element 'Heart Auscultation', then we click on the Boolean operator OR.

We repeat this for the search keywords in the next two boxes. We now see that we have 3 lines, 61, 62, and 63, where the three main elements with their search keywords are combined with OR. Now we can conduct our extended literature search by combining these three lines with AND.

The result of this search gives us now 708 references, compared to our first literature search which yielded 125 references. We have thus conducted a more sensitive search in our chosen database. As a PhD student or researcher, you must, together with your supervisor or your colleagues, consider the scope and relevance of the references found in your first search. If you believe the relevance is too poor, you can conduct a more specific search. In that search, you use the same setup, but exclude the field code for 'abstract' in your free synonymous text word searches. This means that the first text word search that we have had in this example, Heart auscultation*.ti,ab,kw. will now look like this: Heart auscultation*.ti,kw. Here, we have omitted searching in the abstract field, a field that can add some "noise" in the form of irrelevant literature. When we remove the search field for abstract from our search setup, we end up with 396 references. Thus, we carried out a more specific search.

Step 5: Adapt the search to other databases

For many PhD projects or systematic literature reviews within health science disciplines, the databases Medline, Embase, PsycINFO (on Ovid's interface), CINAHL, Web of Science and Cochrane will be relevant databases. If you are unsure about which databases to choose, you should talk to your supervisor or your colleagues, or contact the University Library. A single database is rarely sufficient to search at this level.

The interface of the mentioned databases can feel very different, but the 5-step method as explained above can be used in any of these reference databases.

We will now convert our example search from Medline to Embase Classic+Embase. From our example, you now know that Medline uses MeSH terms to index articles, so that we can easily find relevant references. Embase, which is also on Ovid's interface, uses a different controlled search vocabulary, called Emtree. When moving from one database to another, therefore, one must look up the controlled search keywords found in the database initially searched. In our example, we must find Emtree terms that correspond to the MeSH terms we used in the Medline search.

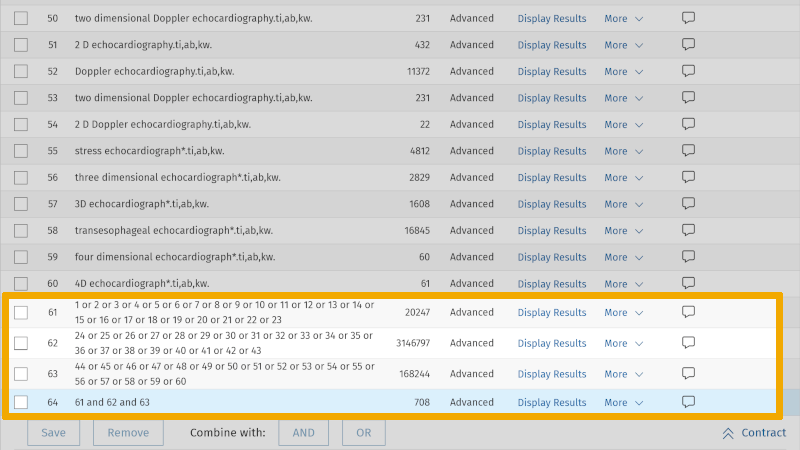

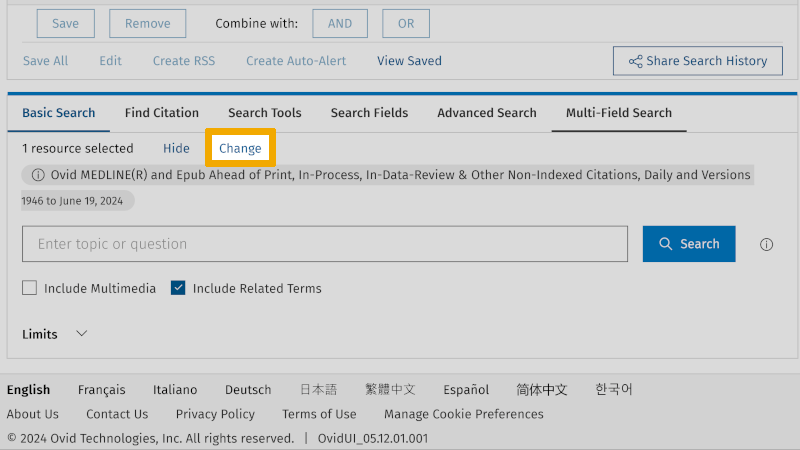

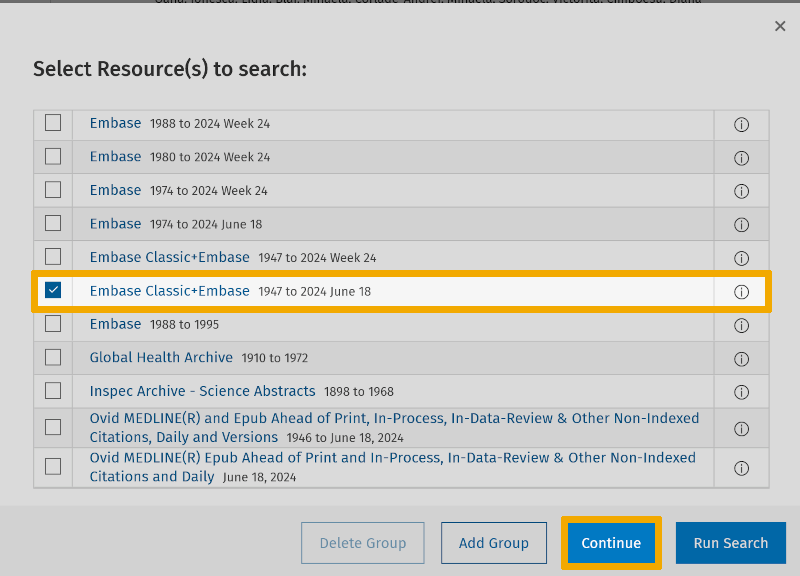

When you now conduct this search in Embase, you must check that each controlled search keyword has a corresponding controlled search keyword in Embase. That is, if there is a corresponding Emtree term. If you have already conducted your search in Medline and saved it, you can now click on the ‘Change’ button to the right of ‘1 resource selected’.

You will then get a new window where you select Embase Classic+Embase. Then you get the choice to click on ‘Continue’ or ‘Run Search’. We recommend that you click on ‘Continue’. The reason for this is that ‘Run Search’ will conduct your Medline search in Embase, without you having quality assured whether the controlled search keywords from Medline are used as controlled search keywords in Embase. By clicking on ‘Continue’, you start a new search in Embase, and you will then have full control over each step in the search process as described above.

To illustrate that there can be differences between the naming (and level in the hierarchical structure of the controlled search keywords), we take the controlled search keyword ‘Echocardiography’ that we found as a MeSH term in Medline. Below you see the hierarchical structure of this controlled search keyword from the MeSH database in Medline.

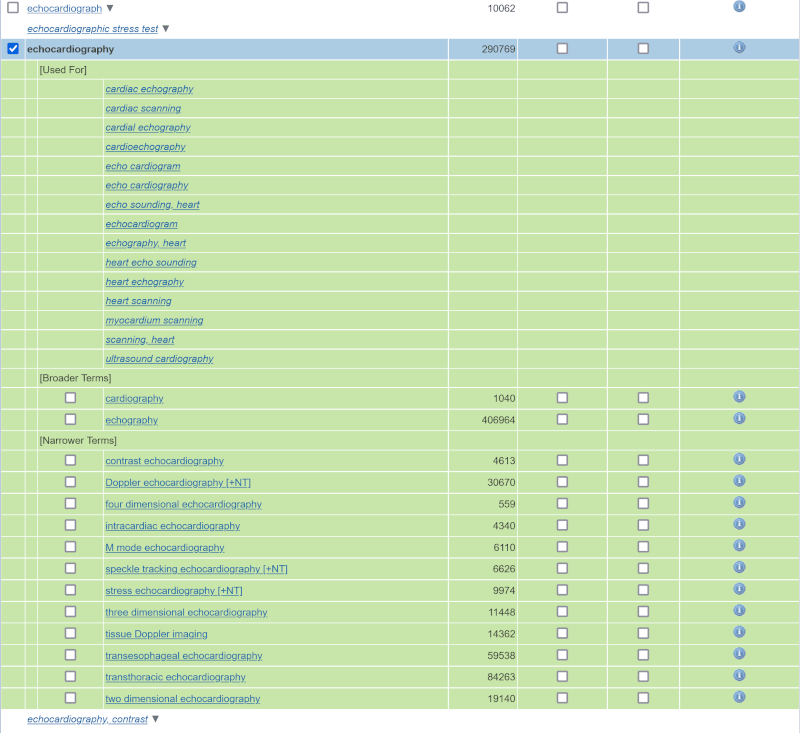

When we look up the controlled search keyword in Embase Classic+Embase, we find a somewhat more complex structure, with more sublevels than we did in Medline.

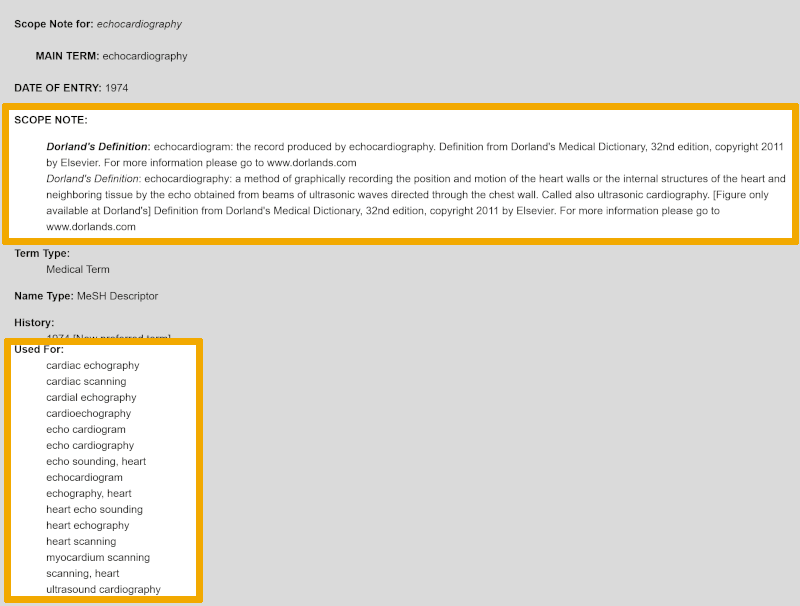

To ensure that the definition of the controlled search keyword ‘Echocardiography’ in Embase matches the definition we found for the MeSH term in Medline, we click further on the information icon under ‘Scope’.

Here we can read that the proposed Emtree term ‘echocardiography’ is defined exactly like the MeSH term ‘echocardiography’ (remember the ‘Explode’ assessment!). Additionally, this Emtree term has a longer list of synonymous text words, which you find under ‘Used for’. These should be considered for inclusion in the search, as synonymous text words. Just like in Medline, you can search in the title, abstract, and authors' keywords in Embase, by using these synonymous text words.

If you find new free search keywords that you have not used in previous searches when you, as in this example, move from Medline to Embase, you should consider including these in your original search setup, and conduct a new search in Medline. We do not demonstrate this in our example, but this is something you need to be aware of. The point is that when transferring a search from one database to another, the searches should be as similar as differences in search vocabulary and syntaxes allow.

Just like in Medline, you can search in the title, abstract, and authors' keywords in Embase, by using these field codes: ti,ab,kw.

Example from PsycINFO, ERIC & Web of Science

We base this on the following example of a project:

Interventions targeting school belonging in secondary education: A systematic meta-analytic review

Step 1: From research question to searchable terms

Before you start identifying search terms, it is important to break down your research question into its main concepts. Ask yourself the following question: Which concepts in the research question must be mentioned in a source for that source to be considered relevant?

In this example, we can identify the following main elements:

- School belonging

- Secondary education

- Interventions/Intervention studies

Note that sometimes, based on what we learn throughout the process, we may need to take a step back and reconsider which concepts are the most suitable to build a literature search around. In this example, we could proceed with the elements we initially identified.

To systematize these main concepts and prepare for finding search terms, we recommend putting the main concepts as headings in separate ‘boxes’. This provides a good overview of the individual search terms and helps you conduct the search in a structured way.

Step 2: Find search keywords for each main element

Now we can begin the work of finding suitable search terms. Since the search tools and research literature will primarily be in English, we need to have search keywords in English.

There are many methods for identifying good search keywords. An obvious first step would be to reflect on this yourself and consult your supervisor and knowledgeable colleagues, or perhaps a chatbot. We can also use dictionaries (e.g. ordnett.no) or online translation services to find good translations of keywords from one language to another.

In our example, we will initially use this most obvious method: noting down the keywords that come to mind based on our somewhat limited prior exposure to the relevant literature. We then have...

The second method for finding search terms mentioned in the general description of the 5-step method is to use the controlled vocabulary interface of a selected database. This is important and useful for at least two reasons: First, we can identify good controlled search keywords, if they exist. We should always use controlled keywords whenever possible. Second, we can also become aware of additional synonyms (often listed as 'entry terms' or 'used for' in the explanations of the controlled terms) for the terms we already have.

Our research question lies at the intersection of educational research and psychology. We could choose a database like ERIC (Educational Resources Information Centre) to start with, but in our specific example, PsycINFO may provide equally good coverage. The choice therefore falls on PsycINFO, as it offers a much better search interface and functionality (on the Ovid platform) than the alternatives.

If you are unsure which databases are most relevant for your own project, you can contact the University Library or discuss it with your supervisor or colleagues.

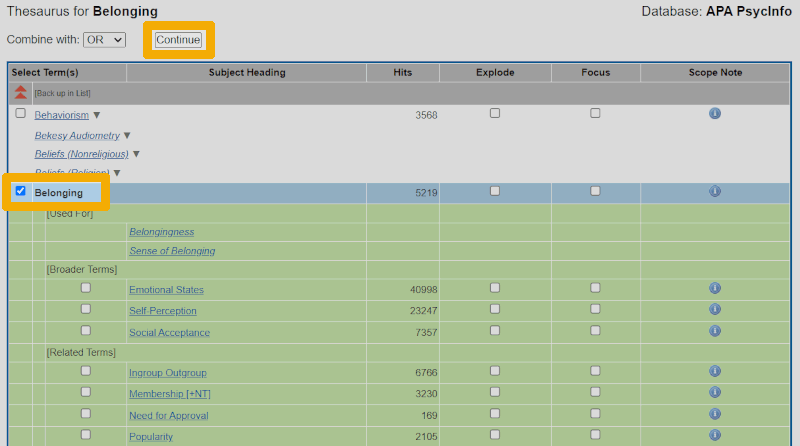

We start with the concept or main element that is the most distinctive thematic part of this research question, namely 'school belonging'. We first try to see if the controlled vocabulary in PsycINFO (whose official name is Thesaurus of Psychological Index Terms) contains keywords corresponding to this main element.

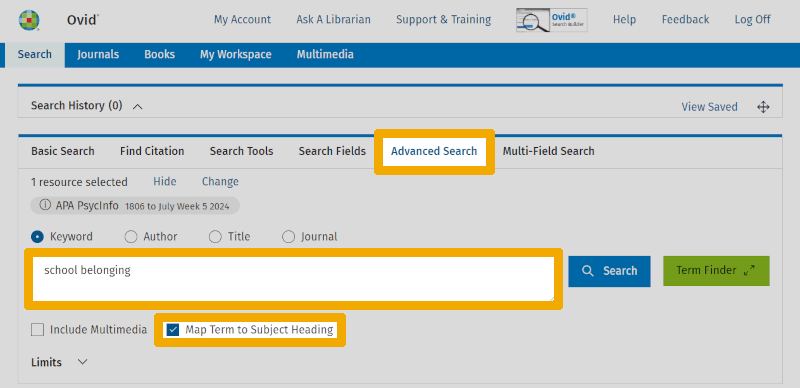

We navigate to PsycINFO from the database overview in Oria. Here, we select the 'Advanced Search' tab and ensure that the 'Map Term to Subject Heading' box is checked. We test an obvious keyword candidate ('school belonging') in the search box:

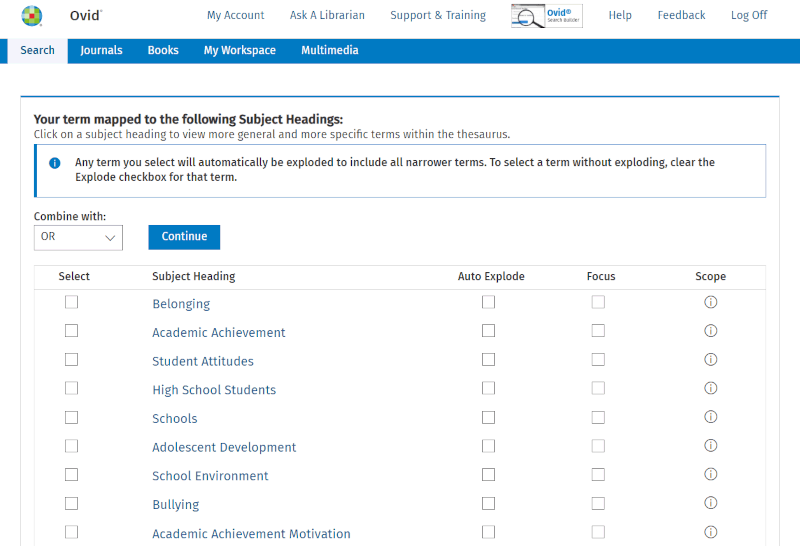

When we now click 'Search', we are not directly searching the database of publications but are asking to "map" or link what we have entered in the search box to potentially useful terms from the controlled vocabulary. The mapping algorithm now provides us with a list of suggestions:

Sometimes the suggestions are few and relevant, while at other times there are no reasonable suggestions. In this case, there are quite a few suggestions, but only a few are relevant. Belonging is the only one we consider worth exploring further here.

To learn more about this controlled keyword, we click on the hyperlinked word 'Belonging' in the list of suggestions. This gives us the following view:

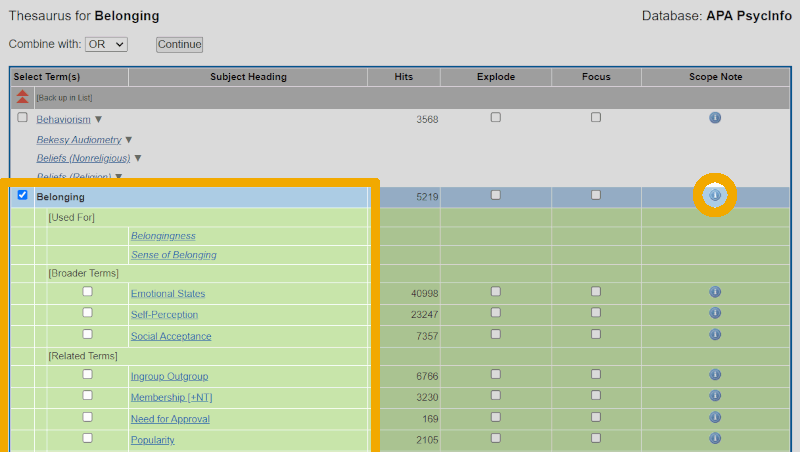

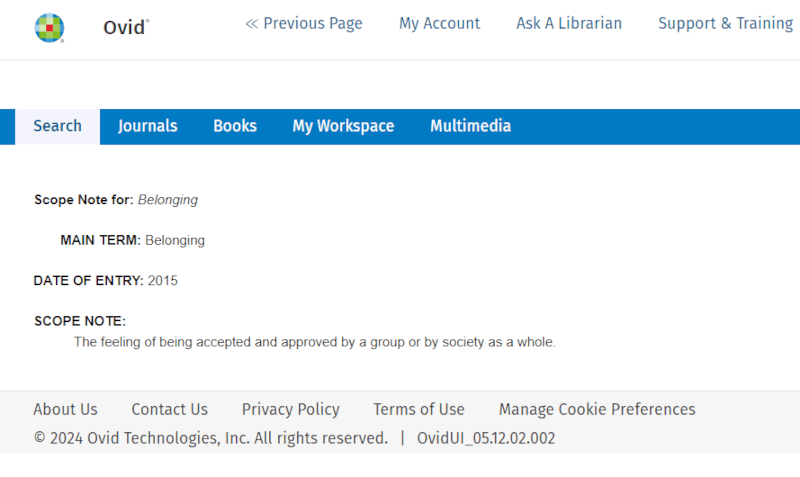

We see from this that the controlled term 'Belonging' is used for, among other things, 'Sense of Belonging', which was also one of the candidates in our own, initial search term suggestions. On this screen, we can also check whether the keyword we are investigating has broader terms and/or narrower terms in the subject heading hierarchy. It is a good practice to always check this. Furthermore, we see that there is a column on the right labeled 'Scope Note'. If we click on the blue circle with the 'i', we get a bit more information about the keyword. Again, it is good practice to always do this for terms we are considering using in our search. If we do this here, we get the following view:

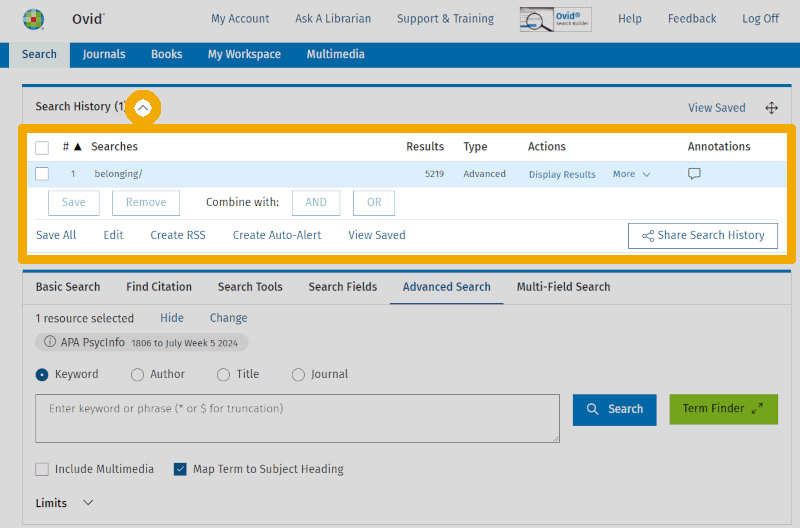

Here, we often find a definition and, sometimes, other important information about how the keyword is used in the indexing of articles in the database. The definition here tells us that the controlled search keyword 'Belonging' (and its synonyms 'Sense of Belonging' and 'Belongingness') is defined relatively broadly and without reference to anything school-related. Nevertheless, we decide, with some hesitation, to use the keyword. We navigate back in the browser to the previous screen, check the box for the keyword to select it, and then click 'Continue'.

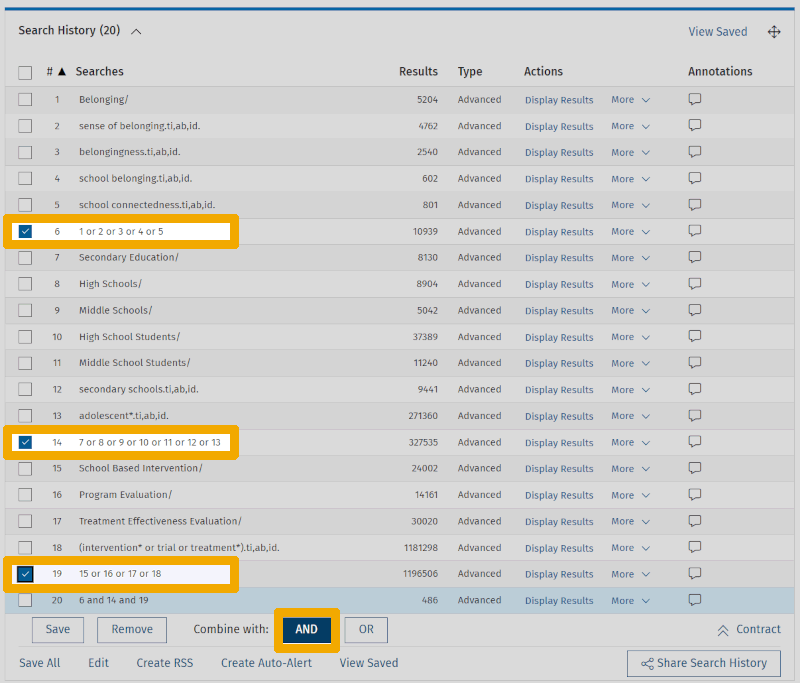

We are then taken back to the 'Advanced Search' screen. We have now retrieved the records for all 5,219 documents that are tagged with the controlled keyword 'Belonging/' in PsycINFO. That list begins immediately below the search box (though we do not see it in the screenshots here). We can now also expand the search history by clicking on the small arrow next to 'Search History' above the search box. We should always have the search history visible when working with searches in reference databases. It is a crucial tool for maintaining an overview and building a clear and well-structured search.

We have now conducted an initial search using a single controlled search term that we think might fit our first main concept/element, school belonging. We have also noted—from the overview within the thesaurus—that this term has the synonyms 'Sense of Belonging' and 'Belongingness'. At the same time, we have discovered that there is no controlled search keyword specifically for school-related feelings of belonging.

We now repeat this process for the other two main elements. We won’t show every single step but will skip to the stage where we have noted both relevant controlled search keywords and some additional possible synonyms. At this point, our notes look like this:

The third method for finding good search terms is a very clever one. It involves using articles we know are relevant, if we have them or can access them. Perhaps you already have a couple from previous, incidental contact with the literature, perhaps your supervisor has recommended some, or maybe you’ve done some simple, intuitive searches in easier tools like Google Scholar, Oria, Keenious, or the 'Basic Search' tab in the Ovid databases. We can then look up these articles in the database we are searching in and see what subject headings they have been assigned there.

This method can be used in several steps of our 5-step method. In this example, we will save it for Step 4: Improving the search.

We now have enough keywords noted down to make a first attempt at building a decent search.

Step 3: Build the first search

We now have a collection of keywords, primarily based on our own somewhat naive intuition and our exploration of suggestions from the mapping algorithm of the controlled vocabulary in PsycINFO. This has resulted in the following collection of keywords:

We will now enter the terms as searches in PsycINFO, one main element at a time and one term at a time. Note! A common mistake is to create overly complex keyword combinations too early. To maintain clarity, it is important to proceed step by step.

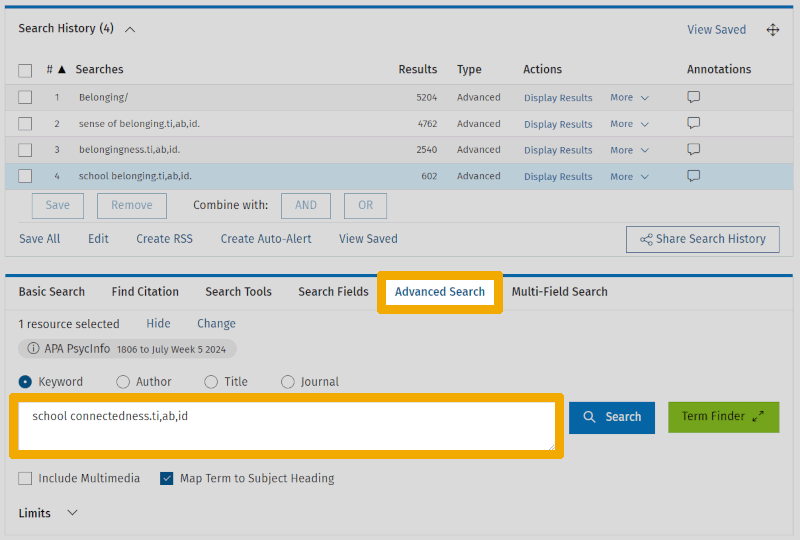

We enter the controlled terms (the subject headings) as we demonstrated for Belonging/ in Step 2. There are several ways to enter the non-controlled terms. Here, we show one common method using the keyword 'school connectedness'.

On the advanced tab, we type the search keyword into the search box. But before we click 'Search', we add what are called field codes, like this: .ti,ab,id. These stand for title, abstract, and the authors' own keywords (which in PsycINFO are misleadingly called 'Key concepts' and, inexplicably, have the field code id). These three fields are the typical choice for free-text (non-controlled) keywords. Note that the codes for the same metadata fields may differ in other databases.

(By selecting the 'Search Fields' tab, you can see an overview of all the searchable fields in the database and their field codes. This can be useful for a variety of slightly more specialized searches.)

Note that the search history already has four lines, one for each of the previous keywords in the School belonging box from our notes.

When we now click search, we skip the mapping phase we utilized in Step 2. (The interface does this automatically when the search box contains a field code or an operator.)

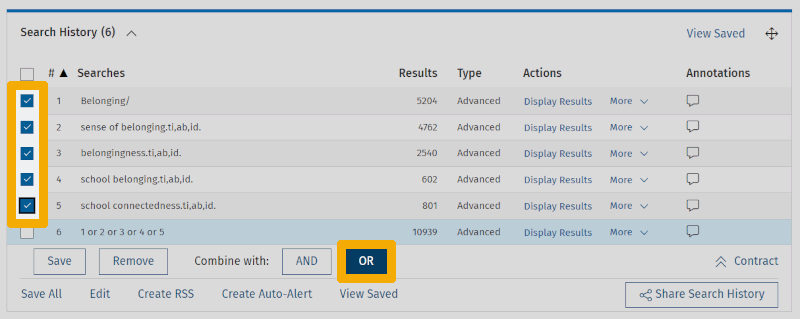

The search history now gets its fifth line. (The first line then disappears upward, and we need to click 'Expand' in the lower right corner of the search history to view it in its entirety.) Now we can combine the keywords we currently have for our first main element by checking the boxes next to each line and clicking the OR button to the right of 'Combine with:'.

We repeat all of this for the other two main elements. For each main element, we first enter controlled terms using 'Map term to subject heading', then free-text terms using field codes. We end up with the following search history:

Notice how we have grouped the keywords for each main element into "clusters" or blocks, which are first combined with OR individually (lines 6, 14, and 19), corresponding to the box structure we outlined in Step 1. Finally, we combined the three collected main elements with AND to find what lies at their intersection (line 20).

This is a decent first attempt, put together with relatively little effort and research. The number of results is relatively modest. However, when we skim through the results list to get an impression of how well the search performs, relevant results are few and far between. This indicates that there is significant room for improvement.

Step 4: Improve the search

In Step 2 of this example, we used two different methods to find suitable search terms. We relied on our own somewhat naive intuition, and we utilized the database's tools to find, understand, and use controlled search terms.

The third method for finding search terms is perhaps the smartest of all: using articles we already have, and that we know are exactly the kind of articles we want to capture with our search. This method, of course, requires that we actually have such articles.

Most people embarking on a systematic literature review have at least some familiarity with the literature they aim to summarize and therefore usually have a small handful of thematically relevant articles. Alternatively, we can take advantage of more "helpful" search tools, where machine learning, natural language processing, and relevance ranking boost naive searches and serve up thematically relevant results. Examples of such tools include Google Scholar and Keenious. The point is that we should have a small handful of relevant articles that we know are the kind we want to capture, as we can then use them to improve our search.

In this example, we have a review article with roughly the same research question as our own, from a few years back. (Our ambition is to create a better literature review that includes even newer research studies and supplements the review with a meta-analysis.) In the reference list of the slightly older review article, we find several articles that could potentially be included in our own study. We can now use these to see how well our search performs.

We do this by searching for some of these articles individually in the database where we built our initial search, and then checking whether our search captures each of them. If it does, then we have built a search that is sensitive enough. If not, we can check the indexing of the specific article to try to understand why our search did not capture it and what might reasonably be changed in our search to ensure it does capture that specific article.

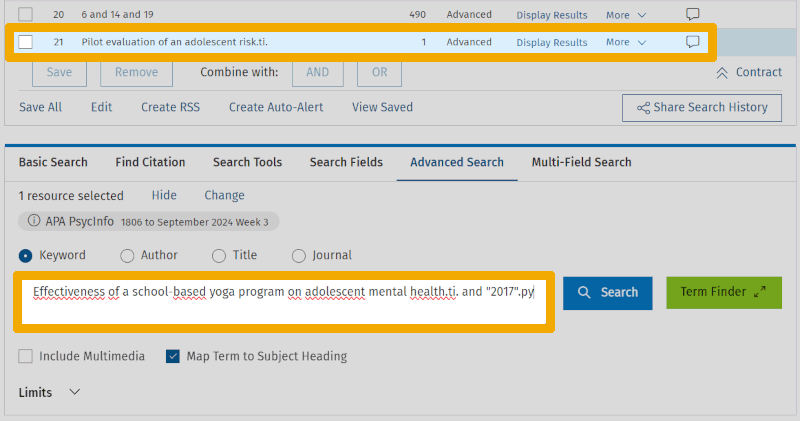

To search for a single article, we can select a segment from the title that we think constitutes a fairly unique combination of words and match this against the database's title field. We will now demonstrate how to do this for two articles we consider to be the kind we want to find with our search.

Here are the references for the two relevant articles:

- Chapman, R. L., Buckley, L., Sheehan, M., & Shochet, I. M. (2013). Pilot evaluation of an adolescent risk and injury prevention programme incorporating curriculum and school connectedness components. Health Education Research, 28(4), 612-625.

- Frank, J. L., Kohler, K., Peal, A., & Bose, B. (2017). Effectiveness of a school-based yoga program on adolescent mental health and school performance: Findings from a randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 8(3), 544-553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0628-3

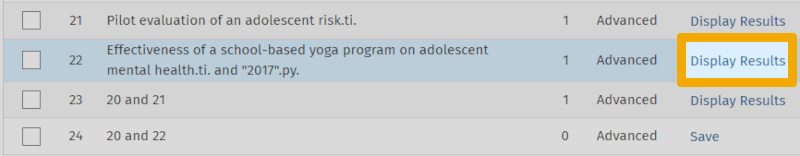

Below our keyword search, we now enter a part of the title from each of them and match it against the title field. In the screenshot below, we have already performed the title search for the Chapman article (it now appears in line 21 of the search history). In the search box, a title string for the Frank article is ready.

Note that for the first article, we only include the first part of the title. This is because if we include "and" (which is the next word in the title), the interface interprets it as an operator, which can cause some issues. Also, note that for the second article, we use the publication year to isolate it, as there were two articles with the same title segment in the database. The lower part of the search history now looks like this:

Note that if we get 0 results from such a title segment search, it means that the article we searched for is not indexed in the relevant database—assuming, of course, that we searched correctly.

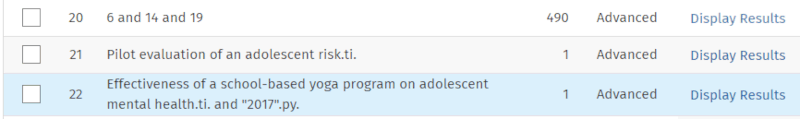

Now we can use the AND operator to check whether the two articles are included in our keyword search. Like this:

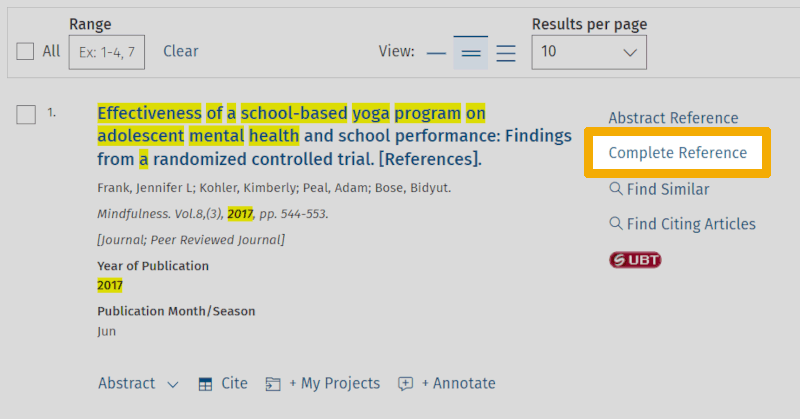

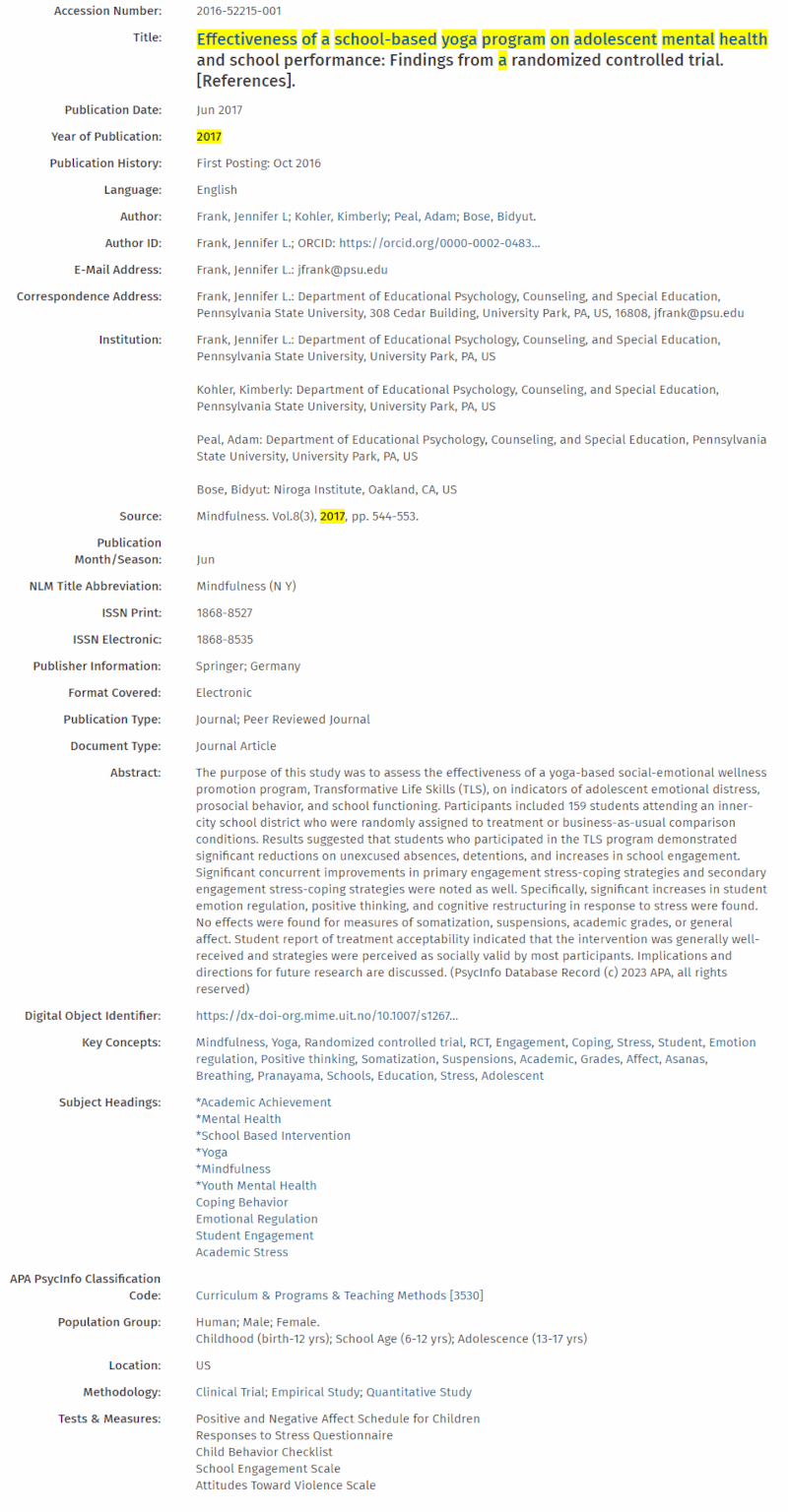

From this screenshot, we can see that the first of the two articles is captured (line 23), while the second is not (line 24). Since we believe that this article should also have been captured by our search, we now need to figure out why it is not. We can do this by clicking 'Display Results' on line 22, so the article appears in the results list:

Then, click on 'Complete Reference' for this article in the results list to view the full record and all the metadata registered for it.

This gives us the following view:

As we can see, there is a lot of metadata here. And yet, we are not seeing everything! A characteristic of this type of database is that they have extensive metadata schemas and very high-quality assurance for the values in all the various fields.

By looking through the record, we see that none of the keywords we used to capture the 'school belonging' concept are represented in the metadata for this article - neither the controlled keyword (Belonging/) nor any of the others. However, we do see that a near-synonym, 'school engagement', appears both in the 'Abstract' field and in a field called 'Tests & Measures'.

This is important information. If we still believe that this article is the kind of article we want to capture with our search, this may mean we need to be more generous with synonyms and near-synonyms to capture articles like this one. By further checking a few more articles, it also becomes clear to us that the general keywords for belonging—Belonging/, 'sense of belonging', and 'belongingness'—rarely appear in the literature on school belonging.

For the other two concepts, there is a wide variety of keywords associated with the metadata of the articles we check. We note all of them and use them to improve the search.

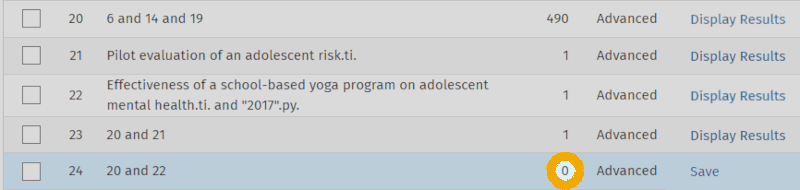

We cannot show the checking process for all the articles here but must settle for illustrating the technique and thought process as we just did. After more research along these lines, we eventually arrive at an improved search. It looks like this:

Notice that we have removed the general belonging keywords from the first part of the search and are now focusing exclusively on synonyms for 'school belonging'. We have gathered all of them into a slightly open proximity search string in line 1.

Also, note that we are taking advantage of a unique strength of the PsycINFO database, namely the 'Tests & Measures' field, by adding the field code 'tm' to the other three.

Additionally, we have added quite a few keywords associated with the other two main elements of our research question.

This results in a search that is both more precise (less noise from belonging that is not school-related) and much more sensitive (more synonyms for school belonging, many more synonyms for educational levels, and many more keywords associated with intervention studies). Our number of results becomes four to five times larger than in the first attempt.

Step 5: Adapt the search to other databases

We are now ready to adapt the search to other databases. Because other databases will have different controlled vocabularies, different searchable metadata fields, interfaces, and operator syntax, we cannot simply copy and paste. In this example, we will briefly demonstrate how our search has been adapted to the educational research database ERIC and the interdisciplinary database Web of Science. We begin with ERIC.

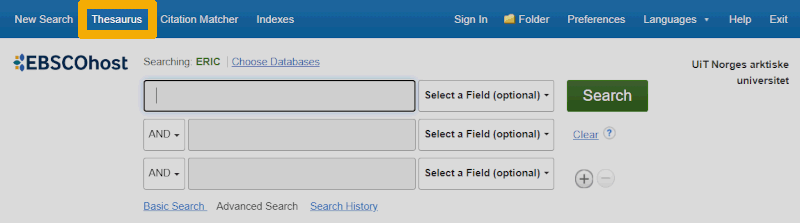

ERIC (Education Resources Information Center) is available at UiT through the EBSCO interface. In the following, we will briefly show how to find and search with a controlled keyword and a non-controlled text keyword. We will then look at the fully adapted search and point out some important differences.

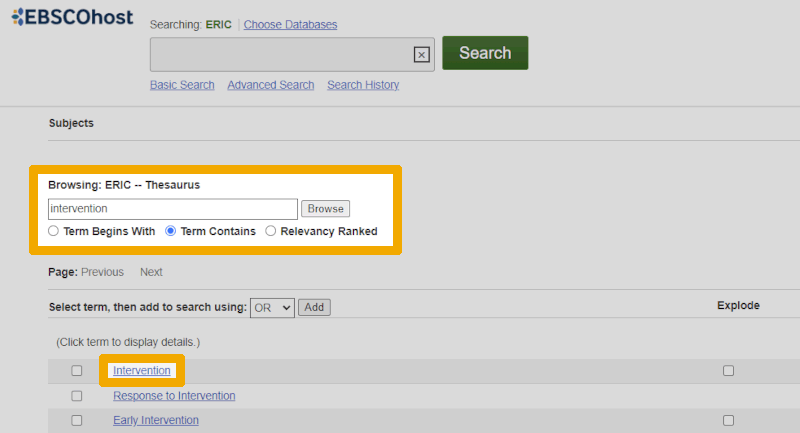

In ERIC, we must select 'Thesaurus' in the blue main menu at the top to access the controlled search vocabulary.

Here, we must make sure to use the lower search box, as it is the one that provides suggestions from the controlled vocabulary. In this case, we have entered "intervention" because we want to see if we can find a controlled keyword that corresponds to this main element. As we can see, several suggestions appear, with the first one being the most relevant. We click on that.

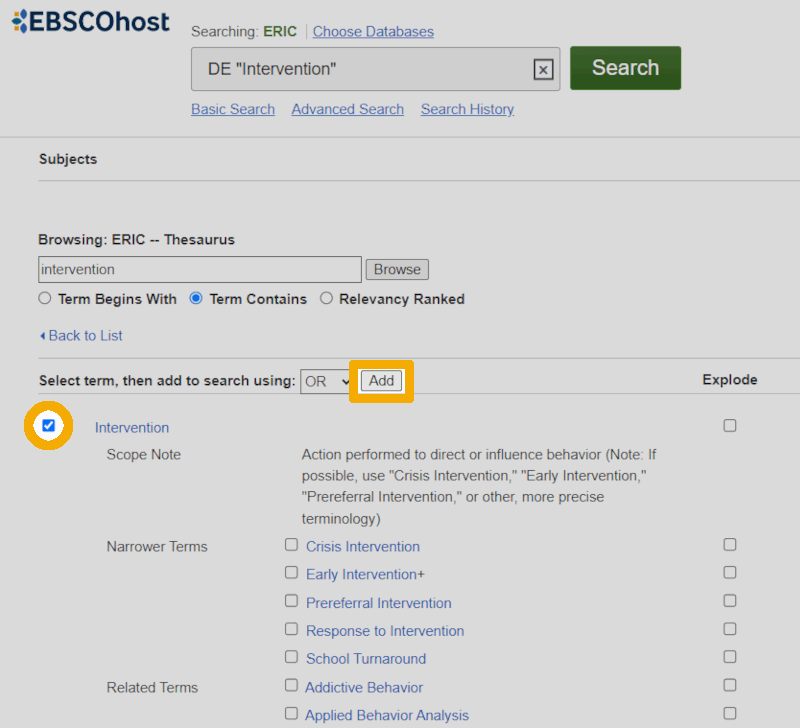

Similar to the Ovid interface, we then get a bit more information about how this keyword is used:

After ensuring that this is a keyword we want to use in our search, we check the box to the left of it and click the 'Add' button. The keyword is now transferred to the top search box with syntax indicating that we are searching the metadata field where the controlled keywords are listed (field code DE in ERIC). We can now click the green 'Search' button next to the top search box to actually perform the search.

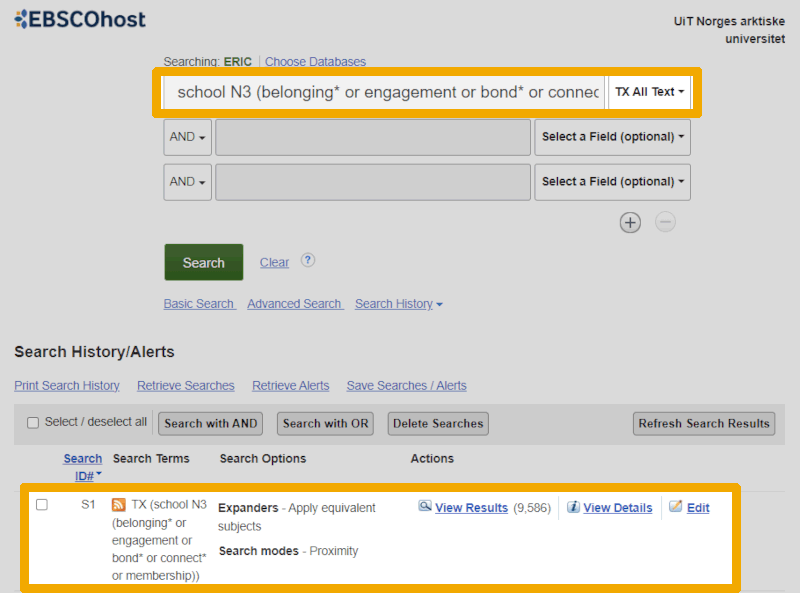

To search for free-text terms (non-controlled search words), it is easiest to use the search boxes on the main page. (We can always return there by clicking the 'Advanced search' link or the EBSCOhost logo.) In ERIC, we can also choose different metadata fields, but we cannot search multiple field codes simultaneously without repeating the keyword or string multiple times. Fortunately, the field code TX (all text) serves roughly the same purpose as searching in title, abstract, and keywords. Therefore, we often choose this when searching for free-text keywords in ERIC. For example, it might look like this for our school belonging string:

The string is the same as the one we used in PsycINFO, but we have adapted it by choosing the corresponding syntax for the proximity operator ("N3" instead of "adj3") and a field code as explained above. We need to click on the 'Search History' link just below the search boxes to expand the search history.

The fully adapted search looks like this:

| Line | Keywords/String | Hits |

| S1 | DE "Student School Relationship" | 5535 |

| S2 | TX (school N3 (belonging* or engagement or bond* or connect* or membership)) | 9414 |

| S3 | S1 OR S2 | 14194 |

| S4 | DE "Intervention" | 58001 |

| S5 | DE "Program Effectiveness" | 74350 |

| S6 | DE "Program Evaluation" | 56981 |

| S7 | TX ("school based" or intervention or program*) | 718724 |

| S8 | TX (trial or assigne* or random* or cluster or crossover or experimental or quasi or comparison or control or matched or "propensity score") | 300951 |

| S9 | AB ("wait list" or treatment) | 48748 |

| S10 | S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 | 921027 |

| S11 | EL (grade N1 (7 or 8 or 9 or 10)) | 22890 |

| S12 | EL (middle or high or secondary) | 193747 |

| S13 | S11 OR S12 | 197225 |

| S14 | S3 AND S10 AND S13 | 2293 |

Here it is presented in a formatted table, as the search histories in the EBSCO interface become incredibly long and unmanageable as screenshots. We can note the following important adaptations:

Unlike in PsycINFO, we have found a controlled term that corresponds to school belonging, namely 'DE "Student School Relationship"'.

We have also found controlled keywords for the other main elements, but since the controlled vocabulary is not the same, they are not identical to those used in the PsycINFO search.

The section for educational level is more compact here. This is because we are utilizing a unique strength of the ERIC database, namely that it has its own metadata field for educational level (field code EL).

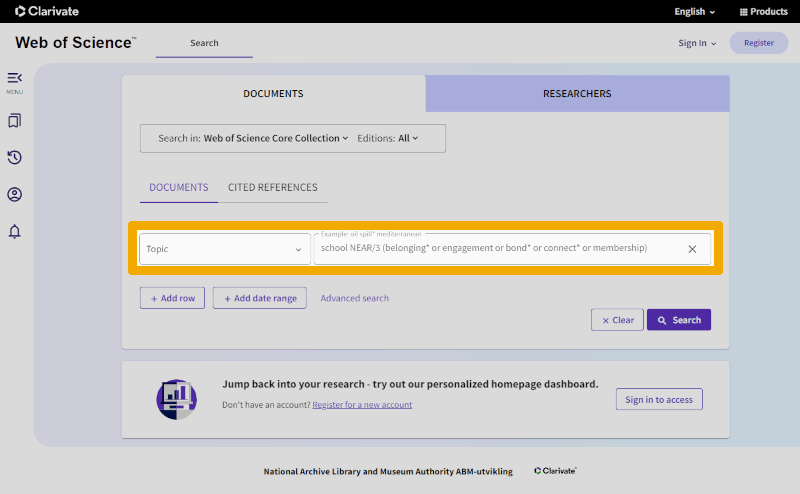

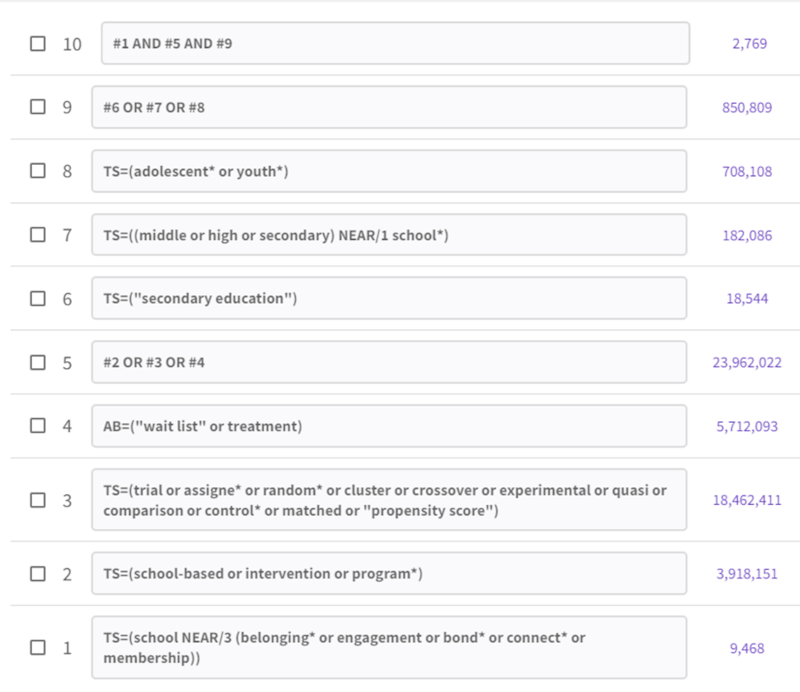

In Web of Science, the differences become even greater because this database lacks a controlled search vocabulary. We are therefore limited to using only free-text search terms against other metadata fields. For most purposes, selecting 'Topic' in the dropdown menu for the search field (field code 'TS=' if using the 'Advanced search' interface) works well. This includes title, abstract, authors' keywords, and Web of Science's Keywords Plus. For our school belonging string, it might look like this:

Again, the string is the same, but now with yet another new syntax for the proximity operator.

To access the search history and the ability to combine lines within it, you must select 'Advanced Search'. On that screen, you will also find an overview of all metadata fields and field codes.

The original search, in its Web of Science-adapted version, looks like this:

Adapting a search in this manner often requires us to consult the databases' search help to figure out field codes, syntax, and other details.