Gap-filling of NDVI time series using SAR predictors and deep learning

Background: The normalised difference vegetation index is defined as , where and are reflectivities measured by a multispectral sensor in a red and a near-infrared spectral band. The NDVI is a dimensionless entity normalised to the interval , which correlates with vegetation greenness, productivity, health status, stress level, growth state, and other parameters. It is therefore used to characterise and predict many different plant properties. It can also be used as an input feature to classification, clustering, segmentation and change detection algorithms.

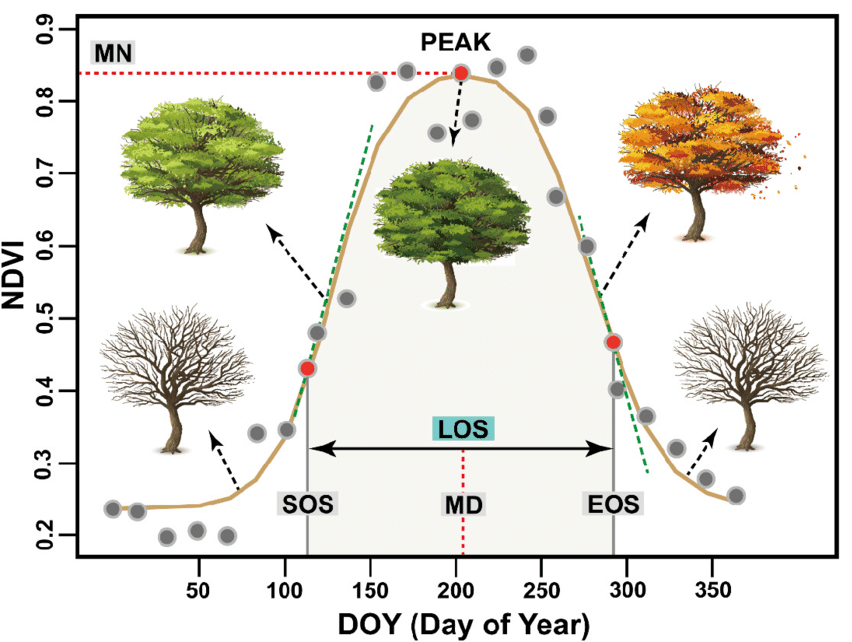

For a given location, the time series of NDVI values observed over one or several growth seasons forms a curve that characterises the evolution of phenological state for that surface. This is shown in Figure 1, which illustrates that the NDVI curve can be used to identify phenological events like the start of season (SOS), end of season (EOS), middle date (MD) or time of maximum productivity (PEAK) (see the red dots and dashed line). From the NDVI curve we can also extract other phenological parameters, such as the maximum NDVI level (MN), length of season (LOS), or the slopes of the NDVI curve at the SOS and EOS time points (green dashed lines). Such parameters are important for studies of vegetation, climate and ecology. Different vegetation classes typically have characteristic phenological parameters, which can then be used by classification algorithms to distinguish between them and map land cover types.

![]()

![]()

Figure 1: Illustration of NDVI curve (brown curve) fitted from satellite-based NDVI observations (grey dots), which has been used to determine phenological events and parameters (see red dots and dashed red lines). Source: Guo et al., Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4538.

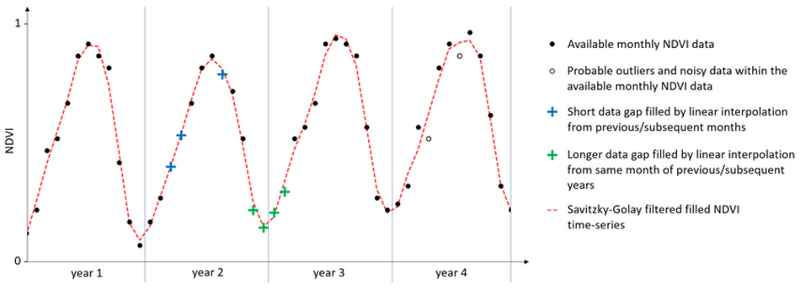

Problem: This project aims to support vegetation monitoring in the High North. The NDVI and optical data in general carry substantial information about plants also in these areas, and the good coverage of polar orbiting satellites at high latitudes provides plenty of data acquisitions. However, high cloudiness strongly reduces the number of useful observations per location. This has prompted the development of compensating techniques, such as mosaicking and gap-filling; Mosaicking combines multiple satellite images with partial cloudiness into one cloud-free NDVI product that represents e.g. one month or one growth season, while gap-filling is the process of completing the NDVI curve by using interpolation and smoothing to fill in the missing observations and recreate the underlying phenological profile. This is illustrated by Figure 2.

Figure 2: Example showing time series of NDVI observations (black dots) spanning multiple growth seasons. Additional NDVI values have been imputed by different interpolation methods (blue and green crosses), outliers and noisy data points have been filtered out and removed (white dots),and the full NDVI curve has been estimated from the imputed NDVI data (red dashed curve). Source: Eisfelder et al., Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3616.

Methodology: The goal is to develop an innovative method that uses deep learning architectures to gap-fill the NDVI curve. One innovative aspect is that we want to use synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data as additional predictors when we interpolate the NDVI curve. This is motivated by previous work on the radar vegetation index (RVI), a parameter formulated similarly to the NDVI, but replacing the optical reflectivities with the SAR backscatter coefficients and , which can be observed at all times, regardless of cloud cover. Time series of RVI values provide phenological profiles akin to the NDVI curve. We assume that the NDVI and RVI curves are correlated, such that the RVI can be used as an additional, external predictor for the NDVI, while acknowledging the decorrelating effect of radar speckle and the different sensor physics.

The other innovative aspect is to perform joint gap-filling and clustering. Clustering will group together pixels that share the same features over time and have the same phenological profile. We can then use NDVI and RVI observations from other pixels as additional predictors to interpolate the NDVI of a given pixel. A possible approach is to formulate one cost function for the gap-filling problem and another one for the clustering problem. A deep learning model architecture can then be devised to optimise these jointly, similarly to the approach taken by [Osa, Moser, Serpico & Zerubia, Proc. EUSIPCO 2025].

Project context: The project will use an analysis-ready dataset from Eastern Finnmark that has been gathered and pre-processed for an ongoing project: “Arctic Forest Futures: An integrative approach to understanding and anticipating ecological transitions in the forest-tundra ecotone (AFF)”. The dataset comprises time series of medium-resolution Sentinel-1 SAR data and multispectral Sentinel-2 data, less frequent but high-resolution lidar data and optical aerial photography, and in situ reference data. It is primarily the Sentinel data that will be utilised in this project, but other data sources can be exploited for interpretation and validation of results.

The development task can easily and flexibly be staged as a capstone project and master’s project. There are opportunities for extending or redirecting the research focus based on the interests of the student. Modifications of the project formulation can be discussed.

Pre-requisites: Good knowledge of machine learning from coursework and practical experience with deep learning frameworks such as PyTorch or TensorFlow.

Supervisors: Stian Normann Anfinsen (stia@norceresearch.no) and Daniel Johansen Trosten, NORCE Research AS

Link to this page